https://www.filmplatform.net/product/yang-ban-xi

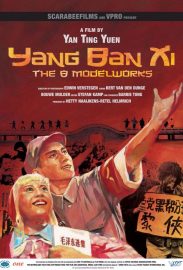

A documentary musical about the rise and fall of China’s colorful propaganda opera’s during the 1965-1975 Cultural Revolution and their renewed popularity in modern day China. Yang Ban Xi is the name given to the eight operas written to celebrate China’s communist revolution. Based on traditional Chinese stories, the operas were adapted into pure propaganda told through beautiful images, incorporating the most modern techniques of cinematography, song, and dance. These operas were the only culture allowed in China for 10 years.

A documentary musical about the rise and fall of Madam Mao’s colorful propaganda opera’s during the 1965-1975 Cultural Revolution in China and their renewed popularity in modern day China.

These 8 Revolutionary model operas were called the Yang Ban Xi. Based on traditional Chinese stories and adapted to the likes of Mao’s wife Jiang Qing Min, the first lady of the Cultural Revolution, these operas the world was presented in a much simpler way. All the good guys were farmers and revolutionary soldiers, singing and dancing in the broad spotlight. All the bad guys were landlords and anti revolutionaries with dark make-up. They were pure propaganda told in beautiful images, incorporating the most modern techniques of cinematography, song, and dance. It was the only culture allowed in China for 10 years.

Although Madame Mao was ultimately convicted as a member of the Gang of Four and committed suicide in prison, the operas have recently regained popularity with the younger generation, who see it as a marvelous mixture of high and low culture. They are performed again and are now also available in Karaoke versions in the Chinese Supermarket.

Exquisite original film segments from the YANG BAN XI, combined with interviews with those who played in them at the time and contemporary performances, open a window into present-day urban China and its burgeoning cultural scene, and make for a visually striking and captivating film.

I don’t exactly remember when I saw a Yang Ban Xi on film for the first time. What I do remember is that its colours and cinematography blew me away. The style and camerawork reminded my of the great Hollywood musicals of the ‘40’s and ‘50s, that I loved to watch as a little girl. Singin’ in the Rain, The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, Hello Dolly, Oliver, I’ve seen them all and I could sing along with every song. Watching that first yangban xi I thought it simply had to be a Chinese musical, and I thought it looked wonderful, even though technically they weren’t as advanced as the western ones. Only years later did I understand the propaganda purposes of these films and all the bad associations attached to them. It was simply not done to just ‘like’ the yang ban xi’s. Therefore, I was pleasantly surprised to hear that nowadays yang ban xi’s are embraced as a specific art by intellectuals and non-intellectuals, in China and abroad. Just one year ago, Heidelberg even harboured an international symposium about the yangbanxi.

There are two things I’d like to state upfront about this film. First, is my intention to make a cheerful film, like the yang ban xi films were. So many documentaries that cover the Cultural Revolution as main or side topics display the horrors of the revolution. These are facts that are undeniable and cannot be ignored or taken lightly. I have no intention of doing so at all. However, what I do want is to approach this subject and its period, like the Chinese people do in the year 2005, with a great sense of humour and irony. This is omething that may be imbedded in the Chinese national character. Not everything was as bad as the western media usually emphasizes, a tendency that irritates many Chinese.

Quite often, I have noticed that the Chinese and Chinese culture are mystified in the

west. China seems to be a country that is made of cliché images and cliché topics here. Who doesn’t know the images of the round hills of Guilin, surrounded by low hanging clouds? Who has never seen the images of the Chinese farmer women with pointed reed hats, who harvest rice in the wet fields, accompanied by a Chinese flute in the pentatonic tone system? Or Chinese on bicycles at the same time crossing an enormous traffic crossing, ringing a cacaphony of bells? The following topics still attract the most attention in western media: Human rights, Falun gong, one-child policy. A correspondent I spoke to in Beijing told me that a topic such as ‘fat children that get sent to weight loss farms at the coast’ doesn’t sell because it simply doesn’t fit in the way the West perceives China. A befriended Dutch-Chinese Sinologist even put it more strongly: ‘The worst that could happen for western media is if China would ever become democratic, the media wouldn’t know anymore what to write about.’

Secondly, I wish to state that I hope to create another image, that of an urbane culture in a modern China. A China that has won the Olympic Games of 2008 (and is tearing down all the old housing districts in the capital to present a clean and

modern capital to the world). A China in which virtually all the teenage girls and boys drink Starbucks coffee on every street corner at a hefty price (because as an only child, they each receive considerable allowances from the incomes of not only their father and mother, but also that of two pairs of grandfathers and

grandmothers). A China in which nothing is allowed, but therefore everything is allowed (as long as you know the right way of getting it). A China filled with contradictions, which tries to unite the old with the new and therefore, pragmatic as it is, has to rewrite history again.

In the end, the film is about a specific period of Chinese history. However, by incorporating the stories of the people in their daily lives, I hope that the film is also about the lives of the people in the present in the cities of contemporary China, a China on the eve of complete participation in the Western world.

Quite often, I have noticed that the Chinese and Chinese culture are mystified in the

west. China seems to be a country that is made of cliché images and cliché topics

here. Who doesn’t know the images of the round hills of Guilin, surrounded by low

hanging clouds? Who has never seen the images of the Chinese farmer women with

pointed reed hats, who harvest rice in the wet fields, accompanied by a Chinese

flute in the pentatonic tone system? Or Chinese on bicycles at the same time

crossing an enormous traffic crossing, ringing a cacaphony of bells? The following

topics still attract the most attention in western media: Human rights, Falun gong,

one-child policy.

A correspondent I spoke to in Beijing told me that a topic such as ‘fat children that

get sent to weight loss farms at the coast’ doesn’t sell because it simply doesn’t fit in

the way the West perceives China. A befriended Dutch-Chinese Sinologist even put

it more strongly: ‘The worst that could happen for western media is if China would

ever become democratic, the media wouldn’t know anymore what to write about.’

Secondly, I wish to state that I hope to create another image, that of an urbane

culture in a modern China. A China that has won the Olympic Games of 2008 (and is

tearing down all the old housing districts in the capital to present a clean and

modern capital to the world). A China in which virtually all the teenage girls and

boys drink Starbucks coffee on every street corner at a hefty price (because as an

only child, they each receive considerable allowances from the incomes of not only

their father and mother, but also that of two pairs of grandfathers and

grandmothers). A China in which nothing is allowed, but therefore everything is

allowed (as long as you know the right way of getting it). A China filled with

contradictions, which tries to unite the old with the new and therefore, pragmatic as

it is, has to rewrite history again.

In the end, the film is about a specific period of Chinese history. However, by

incorporating the stories of the people in their daily lives, I hope that the film is also

about the lives of the people in the present in the cities of contemporary China, a

China on the eve of complete participation in the Western world.

About the content:

The film starts and ends with the voice of Madame Mao, who trumpets the fact that

‘her’ yang ban xi are not forgotten. Throughout the film she gives commentary on

the real people in the documentary, her own life and history in general. In the

documentary she is a fictional character with fictional comments, her comments are

slightly based on real facts of her life. Since her comments are fictional, she is as you

can say in a scenario: an unreliable voice-over. We the audience can see that some

of what she says is distilled with jealousy or revolutionary zest, and therefore not

trustworthy.

The film has a couple of story lines of people, for example:

Mr. And Mrs. Tong: Mr. Tong who made it through the yang ban xi, while his wife was

denied her stage career because of the yang ban xi.

Xue Qing Hua, the ballet dancer who despite all the trouble at least found her

Madame Mao herself who ultimately became the scapegoat of the entire Cultural

Revolution, and lived her life under house arrest until her suicide in 1991, just after she

had seen the yang ban xi on national television again.

Xu Yihui, who still is inspired by Mao and the Cultural Revolution in his works of art and

used to be sexually aroused by the legs shown in Hongse niang ze jun.

It was my intention not to create a dull history lesson, but to make a film about the

people who lived through it and their lives now in modern China.

These are supposed to throw you off guard and also seduce you in kind of way that

the original yang ban xi used to do. Young beautiful people dancing against a

house version of The Red Women’s Detachment. Who can resist that? It’s fun, it’s

joyful, it’s laughter. It should seduce you but also make you feel uncomfortable

(especially in the last scene at the lake).So at times the documentary even takes the

form of its subject: the propaganda film.

Of course at the end of the film, the young artists says something very important: that

art is supposed to make reality tolerable.

Xue Qinghua, The Ballet Dancer

Xue Qing Hua was trained in western classical ballet. At the age of 18 she was

chosen to play the lead in The Red Women’s Detachment (hong se niang zi jun). The

role would make her immortal; Red Women’s Detachment is still one of the most

popular Yang Ban Xi’s. Even today people still know her name. Xue describes this

moment as the most fun but also most stressed of her life. After the Cultural

Revolution she worked as a seamstress, forbidden to dance because of her

attachment to the Yang Ban Xi. Xue married and followed her husband to Hong

Kong where she occasionally still teaches ballet groups.

Tong Xiangling: The Actor

Tong Xiang Ling was a classical Beijing Opera singer and actor when he was chosen

to play the lead in Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy (Zhihuweihushan). He was

extremely popular among the audience and even today he still gives out interviews

about Taking Tiger. While his fame grew larger everyday because of the Yang Ban Xi

during the Cultural Revolution, his wife’s career was denied because of the same

Yang Ban Xi.

Zhang Nanyun: The Opera Actress

While Zhang’s husband Tong Xiang Ling became a star because of the Yang Ban Xi,

her own career stopped because of the same Yang Ban Xi. Before the Cultural

Revolution she was a successful, talented Beijing Opera singer and actress. Her fame

was rising until Madame Mao and her lot, for no apparent reason, denounced her :

well perhaps because she was too beautiful. She was degraded to a ‘black object’

and was never to see the stage again, which she still regrets. After many hardships,

nowadays she and Tong live happily in Shanghai.

Jin Yong Qin-The Scriptwriter

Jin was the notulist of the director when he was suddenly promoted to scriptwriter of

Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy which starred Tong Xiang Ling. It was an existing 4

hour Yang Ban Xi play, which he turned into a 1 1/2 hour yang ban xi movie, all, of

course, under the scrutinous eyes of Madame Mao.He thinks of the yang ban xi as

pieces of unique art. Even if you have the freedom to write what you want

nowadays, it still doesn’t mean you write something lasting and good. Jin now lives in

a small flat in Shanghai and writes television plays.

Zhao Wei-The Guitar Player

Zhao Wei plays the guitar in one of those many Beijing Rock Bands that spurred up in

the 90’s. He used to be in the People’s Republic Army and enjoyed the yang ban xi

very much when he was a kid.

Huang Xiao Tong-The Conductor

Huang is Zhao Wei’s favorite uncle, a retired famous ex-conductor. Being part of the

old establishment during the Cultural Revolution he was locked up in a stable and

forbidden to practice his art form. He tells his story without bitterness, almost cheerful,

as an anecdote. It’s clear he has dealt with history and lives his life peacefully and

happy in Shanghai.

Xu Yi Hui-The Artist & Fan

Xu is a conceptual modern artist in Beijing whose work is often exhibited in China and

the West. His work includes porcelain Little Red Books, exhibited as porcelain kitsch,

turning it into pop art, depicting the shifting values in modern China. When growing

up he used to be a huge fan of the Yang Ban Xi and reveals to us what the youth

really thought of The Red Women’s Detachment.