Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/the-corporation

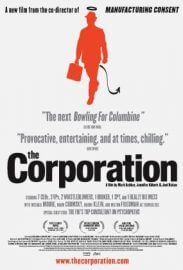

Provoking, witty, stylish and sweepingly informative, THE CORPORATION explores the nature and spectacular rise of the dominant institution of our time. Part film and part movement, THE CORPORATION is transforming audiences and dazzling critics with its insightful and compelling analysis. Taking its status as a legal “person” to the logical conclusion, the film puts the corporation on the psychiatrist’s couch to ask “What kind of person is it?” THE CORPORATION includes interviews with Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein, Milton Friedman, Howard Zinn, Vandana Shiva and Michael Moore.

Part One: THE PATHOLOGY OF COMMERCE

In law, a corporation is deemed a “person”. But what kind of person is it? Like people, corporations have complex “personalities”. With a “personality” of pure self-interest, the past 150 years saw its rise to dominance made possible by a single-minded drive for profit. Four case studies, drawn from a universe of corporate activity, demonstrate harm to workers (sweatshops), harm to human health (the cancer epidemic), harm to animals (synthetic hormone rBGH), and harm to the biosphere. Concluding this point-by-point analysis, THE CORPORATION delivers a disturbing diagnosis: the institutional embodiment of laissez-faire capitalism fully meets the diagnostic criteria of a psychopath. Should the institution or the individuals within it be held responsible? What is the ethical mindset of corporate players?

Part Two: PLANET INC.

Things considered precious, vulnerable, sacred, or important for the public interest once had protective boundaries. But this started to change in the 1600s when the enclosure movement began fencing public grazing lands so they could be privately owned and exploited. Oceans and airspace came next. Today, every molecule on the planet is up for grabs; corporations own whole towns, patents on plants, animals, our DNA, even the song Happy Birthday. When they own everything, who will stand for the public good? Corporations invest billions to shape public and political opinion. Corporate-produced messages reach all of us hundreds, if not thousands of times a day. As one executive states: “You can manipulate consumers into wanting, and therefore buying your products. It’s a game”. New targets are children from the age of three. The ad industry’s “Nag Factor” study shocked child psychiatrists when it exposed premeditated manipulation of infants to “nag” for new products. World disasters can be profitable too. As the Twin Towers collapsed, gold traders doubled their clients’ money. And when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1991 commodities brokers were elated as the price of oil skyrocketed.

Part Three: RECONING

Democracy is a value the corporation doesn’t understand. Corporations have often tried to undo democracy if it is an obstacle to profit. In 1934, a business-backed plot tried to install a military dictator in the White House. It failed thanks to one honest man. Corporations will take advantage of democracy’s absence too. One shocking story is the ‘cozy’ relationship between IBM and Nazi Germany. Corporations are increasingly challenged. The charter revocation movement took on oil giant Unocal; sweatshop activists moved labor standards; seed activists beat corporate patents; and Bolivians defeated Bechtel corporation’s attempt to privatize their water system. Will people regain control over the corporation? With cautious optimism, we are invited to reconsider our relationship with the dominant institution of our time.

My father was a successful small businessman, so I personally have had a life of relative privilege because of the financial circumstances in my family. I’ve always felt an obligation to try to use that privilege responsibly. In addition, filmmakers are very fortunate here in Canada, with the public funding available to us and editorial freedom.

My overriding objective in making The Corporation was to challenge conventional wisdom about the role of the corporation in society, to make the commonplace seem strange, to alienate viewers from the normalcy of the dominant culture allowing them to gain a critical distance on the corporations and the corporate culture that envelop us all.

When it comes to the fate of the Earth, I don’t believe in legitimizing destructive forces by validating their perspective in a “balanced” TV-style journalism format. But I am interested in, and frankly, fascinated by the advocates of economic globalization and corporate dominance. It is essential, in a program of corporate literacy, to hear from them, and to understand their perspective. Reform comes from within as well as without, which is why The Corporation also tries to expose the institutional constraints many good people working inside big corporations struggle with.

Celebrated political filmmaker Mark Achbar rose to fame after his award winning 1993 documentary Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky And The Media. For The Corporation, he teamed up with director, editor and cultural activist Jennifer Abbott (who edited Achbar’s Two Brides And A Scalpel: Diary of a Lesbian Marriage). Based on British Columbia University law professor Joel BakanÅfs book, The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, the film is a powerful critique of modern global capitalism and the conglomerates that feed off it.

Screen International: Did the impetus to make the film come solely from Joel BakanÅfs book or where you looking to make another film along the lines of Manufacturing Consent?

There’s a point in Manufacturing Consent where Chomsky is asked how the media can be made more democratic. He answers that asking how to make the media more democratic is like asking how to make corporations more democratic. “The only way to do that,” he said, “is to get rid of them.” So maybe Chomsky planted the idea for this film by challenging me to question the entire corporate paradigm.

When Joel Bakan and I decided to collaborate on The Corporation, his book did not yet exist. We discovered a shared interest in the subject, he from the perspective of markets and I from the perspective of the impacts of globalization. Joel wanted to write a book and I wanted to make a film. The book was written in parallel to the film, and was completed at almost the same time. So in reality, the film was based on the book, but the book was also based on the film. You could say they co-evolved. Joel was also the writer of the film. While the film drew its core analysis from the book, the book also built on interviews that were done for the film. It was a mutually supportive, symbiotic relationship.

Screen International: How easy/difficult was it to get chief executives to participate?

It was easier to get the former ceo of Royal Dutch Shell to participate than it was to get Ralph Nader ( the US consumer rights activist.) The ceo of Goodyear Tyre, the largest tyre company in the world, was easier to schedule than Michael Moore. These chief executives are organized! They have infrastructure, secretaries, minions. Our Associate Producer, Dawn Brett, made the initial approaches to most of the corporate insiders and her fearless booking skills are such that she convinced them it would be to their disadvantage NOT to be in the film. Which, arguably, is true. Better to speak for yourself than to only have critics talk about you.

But we weren’t out to “get” any individual ceo or corporate insider (they make up about half the 42 interview subjects of the film). Our subject is the institution of the modern business corporation. And to the extent that a given corporate insider could help us shed light on the institution and their role within it–the mindset, the value system, the decision-making–they were more than welcome to participate.

Which is not to say that Dawn just called up any CEO and they said yes. We got plenty of rejections. GM, Ford, BP, Monsanto, HP (we tried to get more women CEOs) and on and on all said no. We wrote to all the top Fortune 100 corporations and asked their CEOs to participate. We also asked them all for free footage. Several were quite helpful.

Screen International: How difficult was it to fund?

The usual misery. It took three-and-a-half years. Though the National Film Board was enthusiastic about the idea, it was rejected. It was rejected by all for-profit broadcasters. There were a lot of pitches. A lot of interest. Few commitments. A lot of paperwork. A lot of begging. We ended up with 15 sources of funding, including my parents.

Screen International: Is George Bush’s post 9/11, post-Iraq II America an easy place to make docs like The Corporation. Where there any particular hurdles to overcome in filming?

It is never easy to make films like The Corporation. 9/11 had a unique impact on the film, first of all, because we were about to board a plane to San Francisco the morning the twin towers were struck. We watched this large-scale spectacle unfold on my cameraman’s one-inch pocket TV screen. There would be a delay of three hours, we were initially told. More likethree months. 9/11 threw an enormous wrench into our production schedule. A pall fell over the business world. People were so depressed it took months to re-schedule to a time when it felt appropriate to talk about anything else. The corporation was ascendant for most of the 90s and 9/11 engendered sympathy for the brokers and other business victims. Corporations also exploited 9/11, donating to the victims, and advertising that fact.

The largest hurdle was coming to terms with such an enormous subject. It’s like making a film about the church in the 16th century. It’s the water we’re all swimming in, it’s the air we breathe. It is all-pervasive. To try to step outside that and look in at this institution with fresh eyes, and make it seem as strange to viewers as it seems to us–that was the real challenge.

Screen International As Bowling For Columbine has demonstrated, the appetite for so-called controversial, theatrically released docs outside the USA is growing, would you say that was the case in the US?

I pray it’s true. It appears to be. When Vanity Fair magazine does a photo shoot for their “Hollywood” issue and devotes a double page spread to “The Documentarians” you know something is going on. The fact we have a theatrical distributor in the US is pretty good evidence too.

Screen International: Is there a common theme that unites all your films?

My films are often broad in scope with multiple points of emphasis. If there is one theme I hope lingers in peoples minds it’s that there is a great deal of needless suffering in the world for which each of us are responsible and we must each do our utmost to reduce this suffering.

Screen International: What’s your next film going to be about and when will we see it?

I haven’t a clue. I’m interested in the phenomenon of “psychedelic” drugs as a pathway to spirituality, but I can’t yet tell if that’s just a personal journey or a subject for a film. I’m deeply offended by the illegality of these substances, as are a growing number of the police who have better things to do, and I’m thinking about how a film might help shift the culture. Maybe someone else is already making that film and will relieve me of the obligation.

But at the moment I cannot yet see the horizon past The Corporation. The DVD, the website, theatrical distribution in Canada, the USA, and Europe, festival screenings around the world… As a producer and a director, they will all require my support. I’m afraid this child has yet to learn to walk on its own. The little brat will need hand-holding for the foreseeable

future.

Screen International: If there was only room for one film on your gravestone what would it be and why?

What a morbid question. As if I would even think about putting my resume on my gravestone! No, I would have a small TV screen built INTO my gravestone with my films playing on it. Or better still, I think I’ll have a TV instead of a gravestone, with an image of a gravestone on the TV and inside that, a little screen with the films playing on that, and inside THAT screen..