https://www.filmplatform.net/product/shock-room

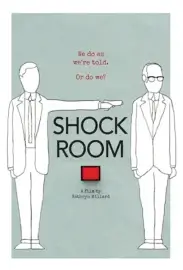

In the early 1960s, psychologist Stanley Milgram, in seeking to understand the Holocaust, ran a series of controversial experiments on obedience. An authority figure orders you to inflict pain on another person by activating electric shocks. Most of us will obey, claimed Milgram. But will we? And were Milgram’s experiments as much art as science? Dramatising previously un-filmed versions of the world’s most famous psychology experiment, SHOCK ROOM turns a light on the dark side of human behavior and forces us to ask ourselves: what would I do?

I first came across the work of Stanley Milgram as a student in Psychology 101—or ‘Rats and Stats’ as we called it. More interested in the behaviour of humans than rodents, I found Milgram’s black-and-white footage of ordinary people grappling with their consciences compelling. So much so that Obedience was one of the films that set me on the path to becoming a filmmaker. But I was always uneasy with Milgram’s conclusions. Were we really programmed to obey?

Fast-forwarding, I worked for screen culture organisations, wrote and directed documentaries and feature dramas, and completed postgraduate degrees in film and history. As an academic I combined—and continue to combine—creative practice with scholarship. For many years, revisiting Milgram’s dramatic experiment sat on my list of ‘One Day’ projects. In the meantime I read everything about it I could get my hands on. As well as the participants who disobeyed, I was particularly interested in Milgram’s work as a filmmaker: How did it shape his experiments? How did his film Obedience shape public understanding of his psychological work? After all Milgram himself acknowledged that his controversial experiment was as much art as science.

In 2008 I began ordering materials from Yale University’s Stirling Library where Milgram’s extensive archive of documents are held. I watched the out-takes of Obedience and read his notes. I remember the excitement of looking at new pieces of the puzzle—from script notes and film budgets to recordings and transcripts. Amongst his papers were lists of scrawled figures as he worked out how to make a film with a shoestring budget. As an independent filmmaker this was a scenario I knew only too well.

Finding the groundbreaking work of social psychologists Steve Reicher and Alex Haslam was an important step. Like me, they did not accept the conventional explanation for harmful behaviour, which goes: ‘I was just following orders’. I asked them to contribute their professional expertise to a film project I had in the pipeline.

From my 2012 micro-budget film, Random 8, I had developed a method of working with actors to restage social science experiments as drama. In 2013 I was awarded an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant (Arts and Humanities Panel) to make a film revisioning Milgram’s landmark experiment. To this end, we built a contemporary version of Milgram’s laboratory set complete with shock machine. As Partner Investigators, Steve Reicher and Alex Haslam advised on psychology.

Fascinating as they are to watch, it is easy to dismiss the participants in Milgram’s 1965 film as historical figures from another era. Not like us. I wanted to bring the Obedience experiments alive for audiences now. In Shock Room, we follow nine fictional characters through contemporary dramatisations. Men and women of different ages, different cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. I cast actors with experience in theatre as well as film, skilled actors capable of sustaining long improvisations. The actors agreed to participate in the project without knowing its storyline. I assured them that they would be safe (and that no nudity was involved). As a director, I consider the trust that the actors placed in me a great privilege. I sketched

Shock Room – Press Information © Charlie Productions 2015 Page 2 of 11

the characters in collaboration with the individual actors to ensure a representative mix of contemporary citizens. The actors then did their own detailed research to bring those invented characters to life. My brief to the actors was that we would be covering them with multiple cameras and shooting extended takes. They were responsible for responding in the scenario moment-by-moment. I cast Simon London as The Experimenter and Martin Crewes as The Learner. I shared my research with them and we spent some time interrogating all things Milgram.

When Director of Photography, Calvin Gardiner and I first talked about the film, we decided it was important to capture each character’s session as a complete entity. We needed a lot of cameras to get angles. We shot with three main cameras behind a one-way mirror to convey the sense of looking in through a window in the laboratory. Six Gro-Pros were placed in the set. The most important camera was on the shock machine itself to capture the drama between the teacher and the experimenter.

Sound Recordist James Currie wired everyone for sound. Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher advised on psychology. We shot interviews with them drawing on their own interpretations of the dynamics of obedience and resistance.

Editor Karen Johnson and I shaped the film with an eye to the human drama. At assembly edit stage, Craig Deeker and The Gingerbread Man post-production house came on board. Tess Boughton’s hand-drawn animation brought some of the film’s big ideas to life. Phillip Johnston contributed an inventive jazz score. While Lawrence Horne’s sound design and mix treated the shock machine as a character in the drama.

Fifty years after Milgram’s film, we made Shock Room to tell a different story, a new story, about his famous experiment. A story that is as much about resistance as obedience. When I began researching this film, most laypeople and many psychologists accepted Milgram’s findings that two-thirds of us will obey orders to inflict harm on another person when ordered to do so by an authority figure, as gold standard. Incontrovertible. But now, more and more researchers around the world are questioning that. New eyes, new evidence, new insights. Shock Room.

THE 1951 film When Worlds Collide dramatised the catastrophic consequences of an impact between Earth with the rogue star Bellus. Some 50 years later the feature length documentary Shock Room reveals the creative consequences of the impact of art on science… and science on art.

This collaboration, initiated by filmmaker Kathryn Millard who approached psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher, made it possible to put Stanley Milgram’s influential “Obedience to Authority” experiments to the test – and to find the conventional understanding of the results wanting.

Shock Room contends that the experiments do not ‘prove’ that people blindly follow orders, as widely believed. Instead, Milgram’s work reveals that people ‘obey’ if they believe in the goal. Obedience is a choice, as is disobedience.

Milgram’s himself described his experiments as a fusion of art and science. In Shock Room, filmmaker Millard contends that he devised a scenario, designed its theatrical setting, rehearsed his accomplices, and cast randomly selected citizens in a long- running structured improvisation.

“This was ensemble drama on an epic scale as much as it was science,” Millard says. “Influenced by Greek tragedy, the morality plays of medieval century Europe, early reality television (Candid Camera) and the improvised happenings of the 1960s. The experimental design and dramaturgy combined to elicit dramatic behaviour.”

Most psychologists saw no reason to review Milgram’s work. They argued the findings were loud, clear and indisputable. Those who did believe reconsideration was worthwhile could not do so for ethical reasons. “Milgram was as infamous for the unethical nature of his work as he was famous for the scientific and social importance of his work, says Reicher. “You could never do what he did nowadays.”

Haslam agrees. Asking participants to administer progressively stronger – though fictitious – electric shocks to another person would never get past an Ethics Review Panel, keen to protect participants from emotional as well as physical harm. Enter Immersive Digital Realism, the technique Millard developed for the project.

Here, 14 actors worked with the director, Millard, to create characters who have volunteered to participate in a psychology experiment. They explored how the character would act in a range of situations and then brought the character to life in a realistic setting – including a replica of Milgram’s impressive ‘shock machine’. The actors were debriefed after filming, first by Millard and then by Haslam and Reicher who collected data.

One of the 14 actors describes the experience: “I don’t remember exactly when my character bailed out. I do remember afterwards a feeling of regret that I hadn’t bailed out sooner and a determination to investigate my responses. Was it my character who kept going, or me as an actor wanting to prolong the experience? I’m not sure.”

Shock Room – Press Information © Charlie Productions 2015 Page 5 of 11

Haslam believes that Kathryn Millard’s groundbreaking method with actors has the potential to make powerful psychology, as well as compelling films.

All three claim collaborating beyond their expertise enhanced their skills, along with their individual appreciation of the “Obedience to Authority” experiments. Working together clarified Milgram’s intellectual strengths and weaknesses. “Milgram was a brilliant experimentalist and a pretty average theorist,” says Haslam. ‘

Above all, their multi-disciplinary approach enabled them to communicate their new views of Milgram’s profound legacy in a medium as powerful as his own. Clearly, the sum was greater than the parts, concludes Haslam. “It’s three circles: film, psychology and the space in between.”