https://www.filmplatform.net/product/placebo

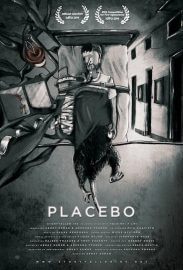

With an acceptance rate of just 0.1%, India’s most prestigious medical school is much more competitive than any Ivy League university. But for these students, getting in is the easy part. Questionable administrative policies, isolation, hazing and intense academic pressure all too often ends up in tragedy. The film is a year-long exploration of life inside campus.

The result? A truly surreal portrait that taps directly into a state of mind. In this case, it’s a state of collective madness—a spell that is only broken when another student succumbs to the academic pressure and does the unthinkable…

When he heard about one of his friends being affected by an act of violence at one of India’s premier academic institutions, Abhay Kumar was both angry and curious to know more. Kumar wanted to investigate.

Landing up at the college, he began talking to students he met there. And soon, he was struck by an idea for his next film. He initiated what he calls a social experiment — surviving incognito inside a top institute’s campus and filming four students through the year to find out about their lives.The footage he managed over 448 days work is now in the next stage of production. The 27-year-old filmmaker, waiting for funding to complete the film, is in fact looking at the crowdfunding route to get some money in. “Rs 500 each from 2000 people is all we need to finish production,” he says.

Testing the hypothesis

How did his adventure start? Equipped with a handycam, a DSLR, an iPhone and an iPad, Kumar closely followed the lives of four students from the institute for over a year to decode their lives. “Don’t mistake this for a reality show, or a video diary. The cameras didn’t follow the students around all the time. They spoke to the camera when there was an event that needed to be discussed. There are a lot of very personal interactions, a lot of conversations,” says Kumar. He reveals that he had little to do with choosing his subjects. “I spoke to several students, but four of them naturally gravitated towards the project. I felt they would open up to the camera. It also helped that all four, who had no connection to one another, had very different outlooks to life. They all came from different backgrounds and were fighting different conflicts,” says the filmmaker.Although he got the students’ permission to shoot, Kumar will not reveal their identities in the film. “My primary duty as a filmmaker is to protect the interest of my subjects who placed their trust in me, opened up to me,” he states, claiming his findings could easily make tabloid headlines.

As far as the institute is concerned, Kumar remained completely undercover. This was the only way he could prevent a knee-jerk reaction from the authorities. “Even though my intention isn’t to do an expose, it was inevitable that the authorities would put an end to my film if they found out,” he says.

Yet, Kumar realised early on that his presence would affect the natural cause-and-effect process. “I started to lose myself in the environment (at the institute) I was to independently observe. I realised that the introduction of an exterior element in an ecosystem alters its natural state,” he says. As a result, Kumar’s personal journey is indelibly tied to the film.

“Come to think of it, I didn’t even go to the institute with the intention of making a documentary film. But when I got there, ideas came to me. I switched on my handycam and just started shooting,” says Delhi-based Kumar.

Of footage and a lack of funds

At the end of the year-long shoot, he is now left with several hours of footage that he must work his way through. “A number of revelations have been made by the students. My film editing and film making work begins only now,” he laughs.

For the entire year and a half that he was on the road, Kumar had managed to fund himself. But now, he needs financial help. He and his associate director Archana Phadke have decided to make this into a hybrid film with a whole bunch of animations and to achieve this and go to the next stage of production, Kumar says he requires about Rs 30 lakh more.

To recover their production costs, Kumar, Phadke and their music composer Shane Mendonca, relied on earlier awards they won for their creative work at international festivals such as Busan. “We never needed to look elsewhere for funding. But now that we do, I think the crowdfunding model works best. The profit-loss margin is very little. In a country like India, surely we can get 2000 people to contribute Rs 500 each,” he says.