Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/look-silence

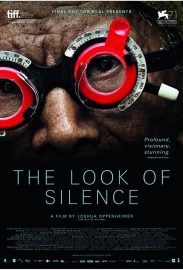

Through Joshua Oppenheimer’s work filming perpetrators of the Indonesian genocide, a family of survivors discovers how their son was murdered and the identity of the men who killed him. The youngest brother is determined to break the spell of silence and fear under which the survivors live, and so confronts the men responsible for his brother’s murder – something unimaginable in a country where killers remain in power.

Description : this is where ramli realized he would be killed

Tags:

Delete EditDescription :

Tags:

Delete EditDescription :

Tags:

Delete EditDescription :

Tags:

Delete EditDescription : the filmmaker engage in an interview with the main character, revisiting the night his brother was killed

Tags: trauma, genocide, indonesia

Delete Edit

The Act of Killing exposed the consequences for all of us when we build our everyday reality on terror and lies. The Look of Silence explores what it is like to be a survivor in such a reality. Making any film about survivors of genocide is to walk into a minefield of clichés, most of which serve to create a heroic (if not saintly) protagonist with whom we can identify, thereby offering the false reassurance that, in the moral catastrophe of atrocity, we are nothing like perpetrators. But presenting survivors as saintly in order to reassure ourselves that we are good is to use survivors to deceive ourselves. It is an insult to survivors’ experience, and does nothing to help us understand what it means to survive atrocity, what it means to live a life shattered by mass violence, and to be silenced by terror. To navigate this minefield of clichés, we have had to explore silence itself.

The result, The Look of Silence, is, I hope, a poem about a silence borne of terror – a poem about the necessity of breaking that silence, but also about the trauma that comes when silence is broken. Maybe the film is a monument to silence – a reminder that although we want to move on, look away and think of other things, nothing will make whole what has been broken. Nothing will wake the dead. We must stop, acknowledge the lives destroyed, strain to listen to the silence that follows.

As an optometrist, I spend my days helping people to see better. I hope to do the same thing through this film. I hope to help many people see more clearly what happened during the 1965 Indonesian genocide – a crime often lied about, or buried in silence. We, the families of the victims, have been stigmatized. We have been called “secret communists,” a “latent danger haunting society,” a spectre to be feared, a pestilence to be exterminated. We are none of those things.

I decided to make this film with Joshua because I knew it would make a difference – not only for my own family, but also, I hope, for millions of other victims’ families across Indonesia. I even hoped it would be meaningful to people around the world.

I wanted my image to be photographed, and my voice recorded, because images and sounds are harder to fabricate than text. Also, it would be impossible for me to meet every possible viewer, one by one, but images of me can reach people wherever they are. Even long after I’m gone.

I knew the risks I might face, and I thought about them deeply. I took these risks not because I am brave, but because I have been living in fear for too long. I do not want my children or, one day, my grandchildren to inherit this fear from me and my family.

Unlike the perpetrators, I do not ask that my older brother, my parents, or the millions of victims be treated as heroes, even though some deserve to be.

I just want my family to no longer be described as traitors in the school books. We never committed any crime. And yet my relatives and millions of others were tortured, disappeared, or slaughtered in 1965.

When I visited the perpetrators for the film, I had no desire for revenge. I came to listen. I hoped they would look into my eyes, realize that I am a human being, and acknowledge what they did was wrong. It was up to them to take responsibility for what they did to my family. It was up to them to ask forgiveness. If, instead, they choose to justify their crimes, adding to the noisy lies, we as a nation, living together in this same land, will have difficulty living together as neighbors in peace and in harmony.

Through The Look of Silence, I only wanted to show that we know what the perpetrators did. We know the truth behind their lies. And one day, the lies will be exposed.

Because we are no longer silent.

– Adi Rukun

The Look of Silence is Joshua Oppenheimer’s powerful companion piece to the Oscar®-nominated The Act of Killing. Through Oppenheimer’s footage of perpetrators of the 1965 Indonesian genocide, a family of survivors discovers how their son was murdered, as well as the identities of the killers. The documentary focuses on the youngest son, an optometrist named Adi, who decides to break the suffocating spell of submission and terror by doing something unimaginable in a society where the murderers remain in power: he confronts the men who killed his brother and, while testing their eyesight, asks them to accept responsibility for their actions. This unprecedented film initiates and bears witness to the collapse of fifty years of silence.

JULY. 17, 2015

“It’s as Though I’m in Germany 40 Years After the Holocaust, but the Nazis Are Still in Power”

Joshua Oppenheimer on how to make an effective documentary about genocide, as discussed with Dana Steven’s at Boats conference 2015.

SEPT. 29, 2015

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the beginning of a mass slaughter in Indonesia. With American support, more than 500,000 people were murdered by the Indonesian Army and its civilian death squads. At least 750,000 more were tortured and sent to concentration camps, many for decades.

The victims were accused of being “communists,” an umbrella that included not only members of the legally registered Communist Party, but all likely opponents ofSuharto’s new military regime — from union members and women’s rights activists to teachers and the ethnic Chinese. Unlike in Germany, Rwanda or Cambodia, there have been no trials, no truth-and-reconciliation commissions, no memorials to the victims. Instead, many perpetrators still hold power throughout the country.

Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous nation, and if it is to become the democracy it claims to be, this impunity must end. The anniversary is a moment for the United States to support Indonesia’s democratic transition by acknowledging the 1965 genocide, and encouraging a process of truth, reconciliation and justice.

Let bygones be bygones!’ Mum and Dad said to me, speaking over each other. Their faces shared a determination to have the last say on the matter. The afternoon light was fading and our teas were turning cold. My parents and I had been shouting at each other for the past hour, debating whether or not Indonesia should apologise to the victims of the 1965 communist purge.

Like some Indonesians who lived through the massacre of nearly one million people that brought Suharto to power, my parents are averse to the idea of a national apology and reconciliation for the crimes of 1965.

‘Who would apologise? All the people responsible have died.’

‘The state,’ I said.

‘It’s in the past,’ Mum snapped.