Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/last-harvest

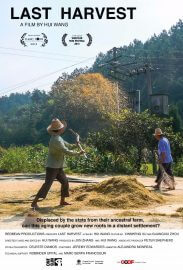

Following the remarkable journey of Mr. and Mrs. Xu, an elderly Chinese farming couple, on a forced relocation by the government’s mammoth South-to-North Water Diversion Project. Lyrical and intimate, the film brings us into the life of two compelling peasants facing major disruption late in life. It continues the story where other documentaries left off – after the people have been relocated and have to re-build their lives, and offers a direct experience of the collision between traditional culture and modernization, through which we see the imminent extinction of Old China as New China emerge.