Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/kims-story

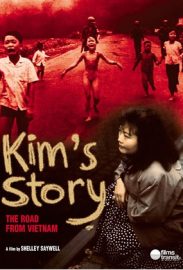

The picture that moved millions all over the world to tears, and that played a major role in the success of the anti-Vietnam War movement, ultimately made Kim Phuc a symbolic figure who was used for many years by the Vietnamese Government.

In telling Kim’s story, Shelley Saywell makes poignant use of news footage of that time, when the dreadfully wounded little girl ran to journalists at the scene for help. She also speaks to the doctors who 25 years ago ensured Kim’s survival, and looks at the personal story which followed this poignant snapshot in time.

Two years ago in Gander, Newfoundland, a young Vietnamese woman disembarked from a plane refuelling from Moscow to Cuba and asked for asylum in Canada. Her name is Kim Phuc and she was the girl on the famous 1972 photograph that brought the world’s attention to the horrors of the war in Vietnam. Today she is in her thirties and mother of a baby boy named Huan. She met her husband Bui Huy Toan when they were both studying in Cuba. Today they live in Toronto and have become Canadian citizens. Kim has been named recently United Nations Goodwill Ambassador. She also recently had a second child.

If there was one photograph that captured the horrific nature of the Vietnam war, one photograph that tore at our collective conscience, it was the picture of a nine year old girl, running naked down a road, screaming in agony from the jellied gasoline coating her body and burning through skin and muscle down the bone. Her village in the Central Highlands of Vietnam was napalmed that day in 1972, and the little girl took a direct hit. It would take many years, and 17 operations to save her life. And when she finally felt well enough to put it behind her, that very photograph would make her a victim, all over again.

The story of that day – June 8, 1972 – and subsequent events in the years that followed will now be fully told on television for the first time.

Kim’s Story is both a universal and a deeply personal story. It parallells the fate of Vietnam itself. Both Kim’s suffering, and her courageous recovery mirrors that of a whole people. It is also the story of how one little girl’s tragedy would be used by all sides. Peace activists, journalists from all over the world, and Vietnamese government officials saw Kim as a symbol, not a person.She wants to tell her story now, just once as a testimony. Then, she wants to move on.

Kim was born in 1963 in the hamlet of Trang Bang, 30 miles north of Saigon. Her full name means “Golden Happiness” in Vietnamese. She remembers happiness despite a childhood of war. On that tragic day in June 1972, the tiny hamlet of Trang Bang was occupied by NLF forces. The South Vietnamese Army’s 25th Division was called in and heavy bombing began. At 2pm the South Vietnamese dropped white phosphorous marker bombs. As she ran with the other children, four drums of napalm dropped on the road. Two of her infant brothers were killed instantly.

“I saw the bombs. I saw the fire. There was a terrible heat,” Kim remembers. “I tore off my burning clothes. But the burning didn’t stop. People poured water over me from their canteens. Then I fainted.”

The AP photographer who captured those horrific moments was Nick Ut. He drove her to a hospital. He would never forget that one little girl. He continued to visit her in the hospital, bring her books and gifts and eventually set up a fund for donations to her family.

The photograph he snapped of her agony was instantly transmitted around the world. It would win him a Pulitzer and change both their lives. Kim would spend the next 14 months in the hospital. She was covered with third-degree burns over half her body and was not expected to live. Her pain was almost unbearable. Her surgeon Dr. Mark Gorney of San Francisco volunteered at the Barksy children’s plastic surgery hospital in Saigon. When he first saw her, Kim’s chin was welded to her chest by scar tissue and her left arm was burnt almost to the bone.

During this period, documentary footage was shot on Kim’s recovery. Her mother was by her bedside, helping the little girl through the trauma. Kim said to herself she would become a doctor like the man who saved her. In this film we will attempt to reunite Kim with Dr. Gorney and photographer Nick Ut, both now living in California. After two years of treatments, Kim returned to her village.

In 1982, ten years after the famous photograph, Kim’s life changed again. She was in pre-medical studies in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) when the Vietnamese government contacted her. They had been looking for her for over a year at the request of a Dutch journalist who wanted to “find the girl in the photograph.” When his subsequent documentary on her revived her fame, they yanked her out of university – deciding she was too valuable to them and daily supervised her schedule as “national symbol of the war.”Every time she tried to evade the officials, another foreign journalist would track her down and expose her. “It was a nightmare” she says.

In 1985 the foreign press corps flocked to Ho Chi Minh City to cover the tenth anniversary of Vietnam’s “Liberation.” Kim was again offered up by authorities as one of their main celebrities, and all three main US. networks carried interviews with “the girl in the photograph.” Finally, in 1986, the government agreed to let Kim continue her studies, under their supervision – in Cuba. Even there she was “managed” and when an American Peace group invited her to tour the United States in 1989, Vietnamese officials cancelled the trip at the last moment.

An article in the Los Angeles Times written in preparation for the tour revived Kim’s fame once more. She received hundreds of letter from American Vietnam veterans “apologising to me.” She met her husband there and they decided to marry. Vietnamese officials gave them permission to honeymoon in Moscow. But secretly she was planning their escape…

All these years later, the photograph of the little girl retains its haunting power. To Kim it is “my photograph, of my own war.” Yet somehow it belongs to everyone; the one image more than any other that turned public opinion against the war. Now, as Vietnam and the United States finally move toward full diplomatic recognition, this documentary hopefully contributes to a process of healing of this century’s longest, most divisive war.