Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/isis-tomorrow-the-lost-souls-of-mosul

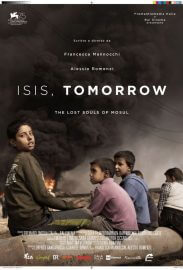

Isis, Tomorrow follows the destiny of the surviving families of the fighters in the complexity of the post-war period, a post-war time of marginalisation and stigma, in which battle blood leaves room for daily revenge and retaliation, for violence as the only response to violence.