https://www.filmplatform.net/product/hitlers-children

Their family names alone evoke horror: Himmler, Goering, Hess.

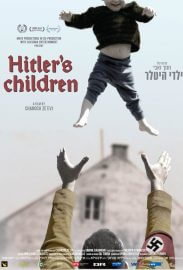

Hitler’s Children is a film about the descendants of the most powerful figures in the Nazi regime: men and women who were left a legacy that permanently associates them with one of the greatest crimes in history. What is it like for them to have grown up with a name that immediately raises images of murder and genocide? How do they cope with the fact that they are the children of Nazis… literally, not just metaphorically.

Niklas Frank

Niklas Frank was eight years old when his father – Hans Frank, which was personally appointed by Hitler to be the Governor of Poland, was hung at Nuremburg for war crimes. Niklas wrote a book about his father: “Der Vater: Eine Abrechnung” which resulted in controversy in Germany because of the scathing way in which Niklas attachd his father, referring to him as “a slime-hole of a Hitler fanatic”.

He lives in Ecklak, near Hamburg, Germany

Bettina Goering

Bettina Goering is the Grand niece of Herman Goering who was a central figure in the Nazi regime and commander of the Luftwaffe.

Like her brother, she had herself sterilized so that the Göring name would one day die out. Bettina now practices herbal medicine in Santa Fe.

She lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Katrin Himmler

Heinrich Himmler, Kathrin’s great uncle, was second only to Hitler in the third Reich, and the mastermind of the Nazi death machine. Katrin Himmler was married to an Israeli Jew. – The son of Holocaust survivors from Poland, and said that she researched about her family past so that her son (born in 1999) would have a full understanding of his family’s history. “When we had our son, it became clear I had to break with the family tradition of not speaking about the past”.

She lives in Berlin, Germany

Rainer Hoess

The grandson of Rudolf Hoess who was the commander of the Auschwitz death camp.

A boxer in his past. Inherited from his grandfather accessories from the Nazi era as well as rare photos which show normal and peaceful life in the villa of the Hoess family in Auschwitz as from 1940, 200 meters from the crematorium. Rainer has tried to sell those accessories about a year ago to “Yad Vashem”, and has aroused great anger for doing so.

Lives close to Stuttgart, Germany.

Monika Hertwig

Monika is the daughter of Amon Goeth – the cruel commander of Plashow – made infamous by his portrayal in the film “Schindler’s List”.

After many years of thinking her father was a “regular soldier” who was killed in the Russian battlefront, Monika found out by accident the fact that her father was a war criminal. From that moment she began investigating her family’s past. While investigating she met by accident a Plaszow survivor named Jan Rozansky who knew her father on a daily basis and told her about her father’s misdeeds which he was eye witnessed to.

Age: 65

She lives in Weissenburg/Bayren, Germany

Eldad Beck

A journalist of the Israeli newspaper “Yedioth Ahronot” in Germany. Third generation to the Holocaust. His family members were killed in Auschwitz. His parents and the rest of his family members live in Israel. Through the years, as part of his job he has tried to meet with Nazi war criminals and their family members.

He lives in Berlin, Germany