https://www.filmplatform.net/product/fallen-city

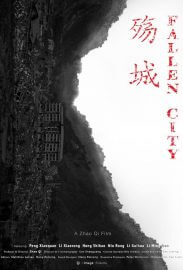

The Sichuan earthquake took 90,000 lives and left 5 million people homeless. Beichuan, once a beautiful valley town, was entirely leveled and nearly every family lost a loved one. But the Chinese construction miracle rebuilt a new city in just three years and what began as a journey to overcome loss becomes entangled with dreams of an upgraded life.

As the survivors emerge from China’s worst natural disaster in decades, they speak for today’s Chinese generation thrust into the nation’s relentless pursuit of progress and violently uprooted from their past.

The Sichuan earthquake took 90,000 lives and left 5 million people homeless. Beichuan, once a beautiful valley town, was entirely leveled and nearly every family lost a loved one. But the Chinese construction miracle rebuilt a new city in just three years and what began as a journey to overcome loss becomes entangled with dreams of an upgraded life. As the survivors emerge from China’s worst natural disaster in decades, they speak for today’s Chinese generation thrust into the nation’s relentless pursuit of progress and violently uprooted from their past.

Director Zhao Qi (Co-producer of the Emmy award-winning Last Train Home) follows three families from the earthquake in 2008 to the completion of the new city of Yong Chang. Peng and his wife lost their 11 year-old daughter and are forced to confront the pressure of carrying on the family bloodline; teenager Hong Shihao, who lost his father, fights a crumbling relationship with his mother and embarks on a coming-of-age journey that questions the meaning of home; Li Guiha, after losing almost her entire family, devotes herself to taking care of her 85-yr old mother and fellow survivors but finds herself lured by the promises of the new city. Combining classic cinema verite with a poetic hand, Fallen City is a beautiful meditation on humanity searching for its place in a changing world.

An introduction to the 3 families

PENG Xiaoquan, 45, Farmer

Mr Peng lost his 11-yr old daughter. After the earthquake, his wife left Beichuan while Peng moved into the mountains with his father-in-law to look after the family farm. Just below the house is the debris hill of the school which buried his daughter alive. Peng often visits her gravestone, burning paper clothes and toys to keep his daughter happy in heaven. When his wife returns a year later, relatives urge them to have another baby. Carrying on the family bloodline is the number one ancestral duty in China and many couples who lost a child to the earthquake were desperate to give birth. But Peng refused to “betray” his baby girl, much to the father-in-law’s dismay. Instead, Peng and his wife rebuild their lives around each other, rediscovering the joys of simply being together, and defining their fulfillment outside tradition. Over time, they begin to accept the thought of having another child. But with the completion of the new city, comes a new trial. As former residents of Beichuan, Peng and his wife get priority allocation for the new flats. But the flats are four times as expensive as the old and there is no way the couple can save enough money by working in the village. Three years after the earthquake, Peng must endure separation again when his wife decides to leave for Shanghai to make money.

LI Guihua, 56, Qiang ethnic minority

Li Guiha is from the Qiang ethnic minority. Like most rural women in China, all she ever wanted from life was a big happy family. But the earthquake took Li’s daughter, granddaughter and four siblings, leaving only her 85 yr-old, wheelchair bound mother – Li’s last link to the past. Strong and vivacious on the outside, Li takes it upon herself to look after her mother and fellow survivors like a second family. She moves into one of the many temporary shelters dotted outside the destroyed old city and becomes head of the neighbourhood committee. For the first three years since the earthquake, she keeps an eye on everyone’s well-being, organises community events and prepares for their transition into the new city. Meanwhile, her mother’s health and memory continues to deteriorate until, finally, she can no longer recognise her own daughter. For Li, once a traditional Chinese woman who depended entirely on her family for a sense of identity, her mother’s loss of memory equated to a loss of a collective memory. Li once said that if her mother had died in the earthquake, she’d have no reason to go on living. But in the final scenes, lured by the promises of a better life in the new city, Li takes an unexpected path.

HONG Shihao, 15, Student

Hong Shihao was 12 yrs old when he lost his father to the earthquake. Months later, his mother moves in with another man, becoming one of the many post-earthquake widows marrying widowers. Early on in the film, Hong proves himself as an understanding young man – “as long he takes care of her, it’s ok with me.” But the relationship between mother and son becomes estranged as they try to reconstruct their lives. Like the millions of Chinese parents who have entrusted all their hopes in their child’s academic performance for a chance at upward mobility, Hong’s mother cannot see beyond his poor grades. Hong escapes her constant scolding by isolating himself in his tiny, cramped dormitory and plugging into the world of online gaming. As the director traces the growing rift between mother-and-son – from Hong’s shy and frustrated attempts at reconciliation to his independence in later scenes, the film hints at the causes and cost of an increasingly individualistic modern Chinese society. Hong eventually fails his exams and loses his chance to go to university. Instead, he goes on to train as a worker for a manufactory line assembling TV sets in Mianjiang, some 200 kilometers away from Beichuan. On his coming-of-age journey, Hong speaks for a generation of Chinese youth alienated from the past and its values and chasing an uncertain future.

Director’s Statement

I was born at the end of Mao’s Cultural Revolution and grew up in Deng’s Open and Reform. It was a period of abrupt and intense change in China. Once instructed by communist teachings, I was later exposed to Western thinking so as a filmmaker I developed a perspective that was different from both the Chinese mainstream ideology and the Western preconceptions of this country and its people.

Thirty years of unprecedented economic boom has lifted the material life of millions, but clouded their hunger for the truth and the reality behind giant propaganda machines. Pragmatism and profit have become essential while humanity and critical reflection have become rare. The real China is as elusive as ever today and neither China’s insiders nor outsiders were given a fair image of this fast-changing nation. But it is my mission to capture glimpses of China’s true human face through the power of film.

Beichuan is one example. The city lost some 30,000 lives in the May earthquake. But added to the tragedy was a lack of compassion and desire to understand what was really lost in the disaster. Much of the population took news reports as exhaustive and quickly turned the Beichuan mourning land into a tourist destination. By giving voice to the survivors, Fallen City gives direct and intimate access to the people behind the statistics and headlines. It is not an exploration of the magnitude of the disaster, but a portrait of human choice and human nature writ large in the wake of a tragedy.

I remember feeling the first jolts in my office in Beijing. An hour later, we learned there had been an earthquake 3,000km away. We were shocked at its strength. The number of casualties reported grew by the thousands with each hour. I’ll remember for the rest of my life, the day when I arrived in the worst-hit city of the earthquake zone, Beichuan. The wreckage was greater than anything in a Hollywood disaster film. Survivors stumbled along with their belongings in a basket; a lady was crawling among the debris of a school, crying for her only son. A man was begging rescuers to stop digging him out because he would rather die with his wife and child, who lay beneath him; a young boy was checking every body bag for his parents. Sirens screeched, helicopters deafened, smoke and dust mixed with the smell of rotten corpses and disinfectants. For a while, all I could do was cry. But then, my instincts led me to film very wide, and long shots, slowly and quietly. It was the only way to make sense of the turmoil and it captured the soul of the disaster.

After a flurry of headlines, Beichuan soon slipped into the dark. The doctors, the soldiers, the volunteers, the journalists – all came and went. The whole country moved its eyes on the Olympic Games and shortly after, Beichuan became a tourist destination. But the survivors’ true story had not been heard. The many twists and turns, the many manifestations of loss and grief that continue years, even a lifetime, after the disaster, ultimately reveal something fundamental about human nature. Fallen City lets the survivors tell their tale. It does not present these characters as victims but as voices of a troubled social and human condition at large. Forced to reconstruct their lives from the rubble, their journey reminds us the importance of choice and purpose as values are so rapidly overturned in China’s great age of progress.

Fallen City is the second film after Last Train Home in my continued exploration and interpretation of what is happening in China and to the individual consciousness during an era of fundamental social and economic upheaval. In the torrents of change and confusion, these films catch elusive truths and offer a candid view into this country.