https://www.filmplatform.net/product/enemies-people

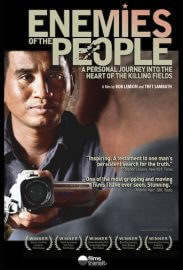

More than simply an inquiry into Cambodia’s experience, however, ENEMIES OF THE PEOPLE is a profound meditation on the nature of good and evil, shedding light on the capacity of some people to do terrible things and for others to forgive them.

It is also a personal journey into the heart of darkness by journalist/filmmaker Thet Sambath, whose family was wiped out in the Killing Fields, but whose patience and discipline elicits unprecedented on-camera confessions from perpetrators at all levels of the Khmer Rouge hierarchy.

DIRECTORS’ STATEMENTS

THET SAMBATH

My father, a middle income peasant, was killed by the Khmer Rouge in 1974 when he refused to give them his buffalo. My mother, forced to marry a Khmer Rouge militiaman, died in childbirth in 1976. My eldest brother disappeared in 1977 in a party purge in our area, I later found out.

When the Khmer Rouge fell in 1979, I escaped – aged 10 – to a refugee camp on the Thai border. I learnt English from American missionaries and eventually started working as a fixer for media organisations in Phnom Penh in the 1990s.

Throughout that time I never really understood what happened under the Khmer Rouge. I read history books – almost all by Westerners – but it still didn’t make sense to me: why were so many people killed? It could not be just because the Khmer Rouge were “bad people.‟

In 1998 through my work as a journalist I got to know the children of some senior Khmer Rouge cadres. For the next four years and much to my wife‟s annoyance, I spent most weekends visiting the home of the most senior surviving leader, Nuon Chea aka Brother Number Two.

But he never used to say anything different from what he told Western journalists: “I was low-ranking‟, “I knew nothing‟, “I am not a killer‟.

Then one day he said me “Sambath, I trust you, you are the person I would like to tell my story to. Ask me what you want to know.‟ For the next five years he told me the truth, as he saw it, including all the details of killing.

Throughout this time I also took pains to create a network of Khmer Rouge killers who would talk to me. There are thousands of people like these in Cambodia but none had ever confessed and finding them is like looking for a needle in the sea.

My last group of sources was the plotters, the people who were trying to overthrow Pol Pot and Nuon Chea. Without them you cannot understand the Killing Fields. But again, none of the survivors had ever talked.

My sources are country people. The Khmer Rouge were all country people. They don‟t talk to people from the city, let alone foreigners. I am a country person. I think that‟s why, in the end, they talk to me. I am one of them.

In 2005 I started to plan a book. But I worried no-one would believe me. So I began tape-recording all my interviews. Then I worried they still might not believe. So, in 2006, I began videotaping my interviews and meetings.

That same year (2006) I met Rob and we decided to make this documentary film about my work and the secrets of the Khmer Rouge.

Some may say no good can come from talking to killers and dwelling on past horror, but I say these people have sacrificed a lot to tell the truth. In daring to confess they have done good, perhaps the only good thing left. They and all the killers like them must be part of the process of reconciliation if my country is to move forward.

ROB LEMKIN

Ten years ago I made a BBC documentary about a mysterious Malaysian revolutionary called Chin Peng. Chin Peng came to London for the premiere and in a taxi back to the airport told me that in 1975 Chairman Mao had sent him to stay with Pol Pot. He told me the truth about Pol Pot was very different from popular opinion. He said Pol Pot was like rabbit in the headlights and admitted to him he was out of his depth after seizing power. That was why, Chin Peng thought, the killing fields had happened.

This image of a genocide caused by chaos and inexperience stayed with me. In 2006 I visited Phnom Penh and met Sambath. I discovered he and I shared the natural revisionism of the investigative journalist. I also discovered he was on the same road to the heart to the killing fields. Only he was much further along; and for him, it was a matter of life and death.

My personal connection with Cambodia is non-existent. But my connection with genocide is not: many of my father’s family died at the hands of the Nazis and a rather remote relative, Raphael Lemkin, even coined the term “genocide‟.

I see Sambath as a man trying to make sense of the nightmare of his childhood. When he finally understands the genocide, as he says he does, he is achieving inner peace and coherence by being able to situate his personal loss in the wider sweep of history.

I also see him as a representative of the Second Generation, working to ferret out the truth from the First Generation, in order to convey the meaning of history to the Third Generation. In this sense this story could be from Germany, South Africa, Northern Ireland, Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Iraq, Sudan.