https://www.filmplatform.net/product/5-broken-cameras

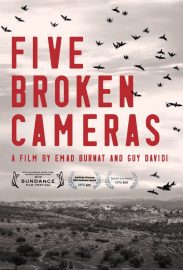

Nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary, 5 Broken Cameras is a deeply personal first-hand account of life and nonviolent resistance in Bil’in, a West Bank village where Israel is building a security fence. Palestinian Emad Burnat, who bought his first camera in 2005 to record the birth of his youngest son, shot the film and Israeli filmmaker Guy Davidi co-directed. The filmmakers follow one family’s evolution over five years, witnessing a child’s growth from a newborn baby into a young boy who observes the world unfolding around him.

The extraordinary story of a Palestinian village’s resistance to encroaching Israeli settlements is brought to life powerfully, eloquently and personally, through the footage from Emad Burnat’s five bullet-ridden and broken cameras. It makes for an intensely powerful personal document about one village’s struggle against oppression.

Like the people in his West Bank village, Emad’s five cameras have been shot at and smashed by Israeli soldiers and settlers. Over a five-year period he has filmed life in the village as a barrier is built across their farmland to separate them from the encroaching Israeli settlement. As Emad and his friends protest peacefully bullets and grenades rain down, but despite daily arrests and night raids, the villagers will not back down.

Cradling this chaos is the touching story of Emad’s new-born son, whose early years are defined by conflict. When, aged five, he asks his dad why the army killed a much-loved member of the community, the insanity of this oppression comes to haunt us. And when, fearing for his life, Emad’s wife pleads with him to stop filming we are bound to their troubled and joyful family life. Despite the seen-to-believed footage, this is an understated personal story told with great dignity.

Emad & Guy join us all the way from the West Bank to discuss their uniquely powerful film, 5 Broken Cameras.

BILIN, West Bank — Emad Burnat was born to the land and, like generations of his family in this hilltop West Bank village, he has eked out a modest living from its rocky soil. But six years ago, at the birth of a son, he was given a video camera and turned unexpectedly into the village chronicler.

Bilin has become the center of popular resistance. There was a great deal to record. Israel was building a separation barrier on village land that included some of his family’s own. The rationale behind it was to stop suicide bombers, but the move confiscated most of the village’s arable land and allowed for the expansion of an enormous Israeli settlement.

Bulldozers uprooted centuries-old olive trees while settlers drove up with furniture and mobile homes. Villagers stood in the way; soldiers arrested them. Mr. Burnat was there, day in, day out, filming with his new camera.

Now, working with an Israeli filmmaker, Guy Davidi, Mr. Burnat has taken his years of video and turned them into a compelling personal tale. The film, “Five Broken Cameras,” won two awards in November at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, including the Audience Award, and is one of about a dozen films competing at Sundance this week in the World Documentary category.

As Bilin became the center for Palestinian popular resistance — weekly demonstrations joined by Israeli and foreign activists, and a partial Supreme Court victory forcing the barrier to be moved and some land returned — Mr. Burnat’s images became crucial. They were used not only by journalists but by those fighting charges in Israeli military courts. Accusations of assault were sometimes countered with a common refrain: let’s go to Emad’s videotape.

The new documentary intersperses scenes of villagers fighting the barrier with Mr. Burnat’s son Gibreel’s first words (“cartridge,” “army”), undercover Israeli agents taking away friends and relatives, and Mr. Burnat’s wife, Soraya, begging him to turn his attention away from politics and be with his family. Over six years, Mr. Burnat went through five cameras, each broken in the course of filming — among other things, by soldiers’ bullets and an angry settler. At the start of the film, Mr. Burnat lines up the cameras on a table. They form the movie’s chapters and create a motif for the unfolding drama — the power of bearing witness. Mr. Burnat never puts his camera down and it drives his opponents mad.

“Tell him if he keeps filming I will break his bones!” a settler declares to a soldier. Mr. Burnat keeps filming. The settler approaches him and, as the camera rolls, throws it to the ground, breaking it. The screen goes blank.

“When I film, I feel like the camera protects me,” Mr. Burnat says in his soft-voiced narration of the movie, making a point familiar to all journalists. “But it is an illusion.”

In one scene, soldiers come to Mr. Burnat’s house (“Now it’s my turn,” he says into the camera) to arrest him on charges of throwing stones and assaulting a soldier — charges he denied and of which he was later exonerated, according to an army spokesman. He films the soldiers’ entry into his house and their surreal assertion that he must turn off his camera because he is in a “closed military area.” “I am in my own home,” he replies. He spends three weeks in prison and six weeks under house arrest. It takes three years for the case to be dismissed.

A subtheme of the film is the activism of Mr. Burnat’s two close friends, Adeeb and Bassem Abu Rahma, who were cousins. Bassem was nicknamed “Phil,” the Arabic word for elephant. Both were playful, big-hearted guys at the front of the demonstrations. Phil was killed at a demonstration in 2009, and Mr. Burnat originally thought of making the movie about him.

But Mr. Davidi and an Israeli organization called Greenhouse, which pairs regional filmmakers with European mentors and is financed by the European Union, persuaded Mr. Burnat to place himself at the center of his story. It was a crucial move that gave the film its power and intimacy. But it did not come naturally.

“It was a very difficult decision to make such a personal film,” Mr. Burnat, 40, said as he sat in the garden of his home. Gibreel, now 6, and his older sons were wandering in and out, and the high-rises of the Modiin Illit settlement could be seen in the distance. “I was uncomfortable about showing footage of my wife. This may be normal in Europe, but here in Palestine you have to answer many questions. I have so far avoided showing the film here.”

Mr. Davidi, the 33-year-old Israeli co-director, first came to Bilin in 2005 to shoot a documentary on Palestinian workers who take construction jobs in the settlement, and he met Mr. Burnat then. “We wanted our film to be an understatement, not to be provocative or combative,” Mr. Davidi said.

The movie’s personal style is not the only issue bringing Mr. Burnat heat. Working with an Israeli filmmaker and taking help from Greenhouse have been controversial. The Palestinian movement increasingly promotes a boycott of all things Israeli on the theory that contact serves to “normalize” relations that should be frozen until progress is made on ending the occupation.

“When we showed the film in Amsterdam, Palestinians and other Arabs came up to me and asked how I could work with Israelis,” Mr. Burnat said. “But from the start, the struggle for Bilin involved Israeli activists.”

Greenhouse, which has sponsored 15 films and has brought together 100 moviemakers from Israel, Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt, Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia and the Palestinian territories, knows that many in the Middle East object to what it does.

Sigal Yehuda, Greenhouse’s managing director, says the issue is discussed openly at the seminars the group sponsors around the region.

“Coexistence is one of the most important fruits of this activity,” she said. “These are intelligent and influential people who have lived with, eaten with and even danced with Israelis.”

For Mr. Burnat, the coexistence question is especially delicate. In late 2008, he accidently drove a truck into the separation barrier and was badly injured. A Palestinian ambulance arrived at the same time as Israeli soldiers, who saw what bad shape he was in and took him to an Israeli hospital.

“If I had been taken to a Palestinian hospital,” Mr. Burnat said, “I probably wouldn’t have survived.” He was unconscious for 20 days. Three months later he was back filming, little Gibreel trailing behind.

“The only protection I can offer him,” Mr. Burnat says of Gibreel at that point in the film, speaking for chroniclers everywhere, “is allowing him to see everything with his own eyes so he can confront just how vulnerable life is.”

Weeks later, an Israeli tear gas canister hit his friend Phil in the chest and killed him.

When we started this project, we knew we would be criticized for working together. Emad would be asked why he chose to make the film with an Israeli, and Guy would be asked why he chose to make the film with a Palestinian. Still, the actual differences between us were something we could not avoid: we have different cultural backgrounds and different privileges, and we had to learn to use them in a constructive way. There are also different expectations for us as a result of our identities.

When we finally decided to make the film, we decided it had to be as intimate and personal as possible. That was the only way to tell the story in a new and emotional way. For Emad, this was not an obvious or simple decision. Exposure can be flattering, but it can also be risky. On the other hand, the film had be focused on Emad’s narrative, with Guy taking the role of storyteller.

We hope that people come to see the film with open minds and without foregone conclusions. When watching a film that deals with such a painful controversy, we know that people tend to shut down. Most of us divide the world into right and wrong, good and bad, Palestinian and Israeli. We immediately take a side that corresponds to our identity, life experience, or ideology, even though these loyalties prevent us from fully experiencing the world. Reality is wonderfully complex, and we become frustrated when people fight to look at it with only one or two filters.

5 Broken Cameras was made to inspire, and not just to be interpreted as part of the political discourse – although it is, of course, an important part of it. We made the film with sincere initiative, trying to challenge our own assumptions and avoid cliché. In the end, we hope everyone will come away with open hearts.