It's no secret the education landscape is experiencing significant challenges. School boards and parent groups in the United States are increasingly pushing for book bans and curriculum restrictions. Across the Atlantic, the UK faces a rise in student absenteeism in the aftermath of COVID-19, and in Europe, student achievement in reading, math, and science is on the decline thanks in part to decades of socioeconomic inequality.

Meanwhile, the United Nations has sounded the alarm on an impending global teacher shortage, predicting that millions of new educators will be needed to meet the demands of a growing student population by 2030. Amid these challenges, teachers and students alike find themselves at the forefront of navigating a complex and often hostile educational landscape.

The most recent federal data from the

U.S. Department of Education's Civil Rights Data Collection indicates that disparities among students have stubbornly persisted, even during a year when many engaged in remote or hybrid learning.

Students part of neurodivergent, racial, disabled, or lower socio-economic groups are still over-indexed on disciplinary action. They report higher levels of bullying or harassment and are more likely to have less access to high-level courses.

It's a perpetual cycle of the "child who starts behind, stays behind". Addressing the achievement gap is not just an educational imperative; it's a community one. Systemic changes are desperately needed but in a world where political, community, and academic sectors are not always working cohesively, educators can still help bridge the disparities that plague our school systems.

Poetically it can start with stepping into the role of the student. Documentaries such as "

America to Me", and "

Paper Tigers" allow us to delve into a range of nuanced issues from students' perspectives, and also explore effective strategies for creating healthier, more inclusive classrooms.

The ten-part docuseries "

America to Me" has proven to be a crucial resource for schools seeking to improve equity in education and close the gap.

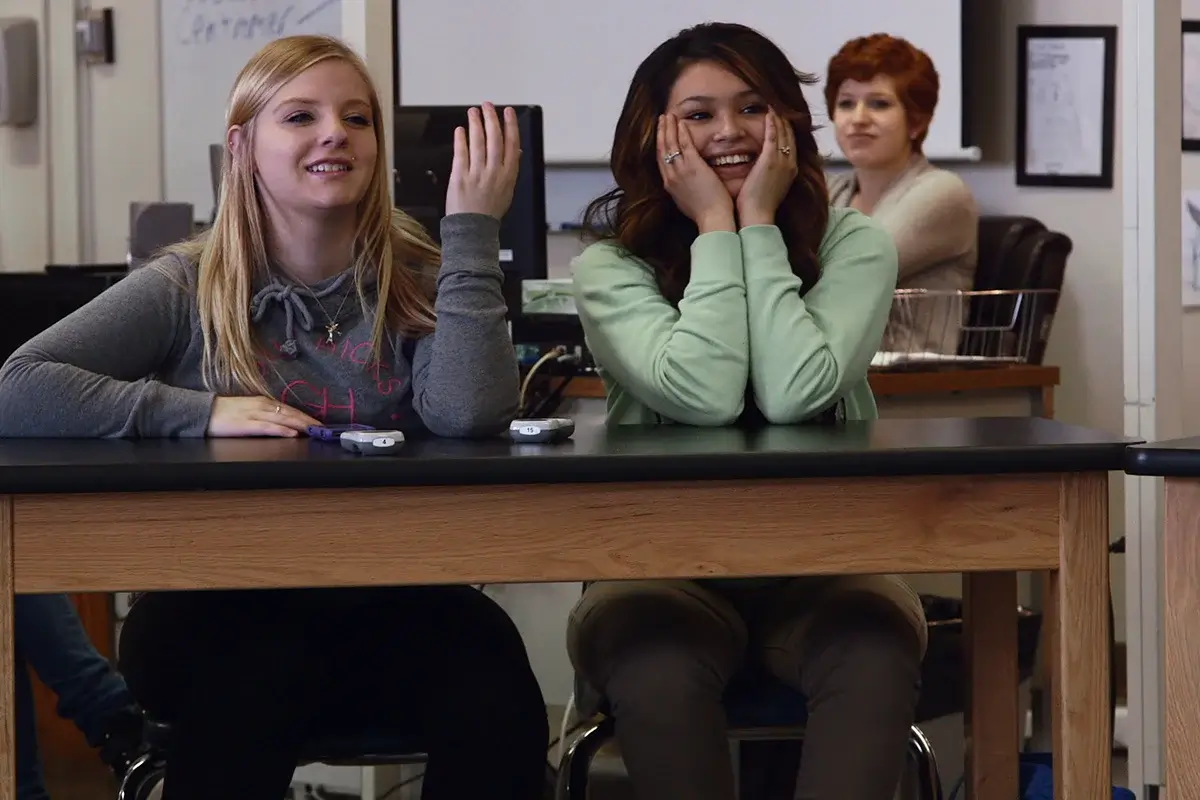

Image from "America to Me"

Directed by Steve James, the series takes a candid look at racial and economic disparities by spending a year closely following students and staff at the progressive Oak Park and River Forest High School in Chicago. The series vividly portrays the barriers to learning students of color still face, and the impact of when psychological safety is not built into school culture.

In the halls of Oak Park and River Forest, a predominantly white school, teachers, students, and parents confront issues of identity and unconscious bias. Investigating through personal interviews and a review of school practices, they unveil a culture that had been not only perpetuating racial bias but reinforcing the achievement gap.

That was certainly felt by student Ke'Shawn Kumsa, who shared his experiences of being profiled by school security and feeling like his teachers had lower expectations of him than his white counterparts. "They see me as a problem before they see me as a person," he says in the film.

Jessica Stovall, one of the teachers featured in the film, now an Assistant Professor of African American Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, emphasizes the importance of building relationships with students to establish trust.

"When you have trust, the kids will open up to you, and they will work for you in a way that they won't work for other teachers who don't try to establish those relationships," she says, reflecting on her approach to fostering a supportive classroom environment.

Jessica Stovall, from the website of the Department of African American Studies

at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

Culturally responsive teaching doesn't just celebrate diversity, it shows up for all students, by integrating diverse cultural references into every aspect of learning. "

America to Me" highlights the need for educators to present diverse narratives, expand teaching reference points, and make space for cultural expression.

Oak Park is not a one-off. Amanda Lewis, Director of the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy at the University of Illinois, and Ford Foundation Professor of Sociology and Education Policy at Brown University, John Diamond were also curious to explore outside of grandfathered societal systems and their effect on the achievement gap.

The pair wrote the book "Despite the Best Intentions: How Racial Inequality Thrives in Good Schools" after five years of research at Riverview High School, a well-funded, progressive school district that wanted to go deeper to understand why, in a school that had a fairly even split on race, Black and Brown students were continuing to fall behind.

"We all have a basic idea of how discipline or tracking practices work, and how parental involvement should work," Diamond told University of Wisconsin's School of Education.

"And we often think of it as being fair and of people being treated fairly. But in the book, we argue that race fundamentally shapes how those routines are actually performed, and that's how inequality gets into the system and is reproduced."

1

They argue that many macro-level issues are familiar, but the way inequality is woven into the everyday behaviors of students, staff, and parents of these school communities is often undervalued.

The big issues are of course not to be ignored. There's a wealth of research that has illuminated the socioeconomic connection between educational opportunities and academic performance.

While the economic gap has been growing over the last fifty years for everybody, researchers have found that the learning environment can have a significant effect on widening the achievement gap - sometimes more so than at home.

2

Poverty is in many cases considered an adverse childhood experience (ACE). Based on a study conducted by Kaiser and the US Center for Disease Control in the 1990s, the AE model is still used by psychologists and many school counselors today.

It can be categorized into three groups: abuse, neglect, and household challenges including traumas surrounding poverty, divorce, mental illness, or exposure to substance abuse.

Yet culturally specific ACEs were hardly considered until more recently, and there's also been limited study on the association between ACEs and education outcomes, though there's no doubt many teachers can identify the correlation.

"

Paper Tigers", explores alternative approaches to addressing behavioral issues and roadblocks many students experience as a result of trauma. Following six students over the course of a year at Lincoln High School, the film spotlights where staff shifted their approach from traditional punitive discipline to one that understands and addresses the underlying trauma affecting students' behavior and academic performance.

Creating a safe space for students to express themselves and heal is a cornerstone of Lincoln High's approach. The teachers are supported with extensive training to provide emotional regulation techniques such as mindfulness and meditation, ensure predictable routines for stability, and create psychological safety in the classroom.

"Instead of asking kids 'What's wrong with you?' we need to be asking, 'What happened to you?'", says Jim Sporleder, the principal of Lincoln High School.

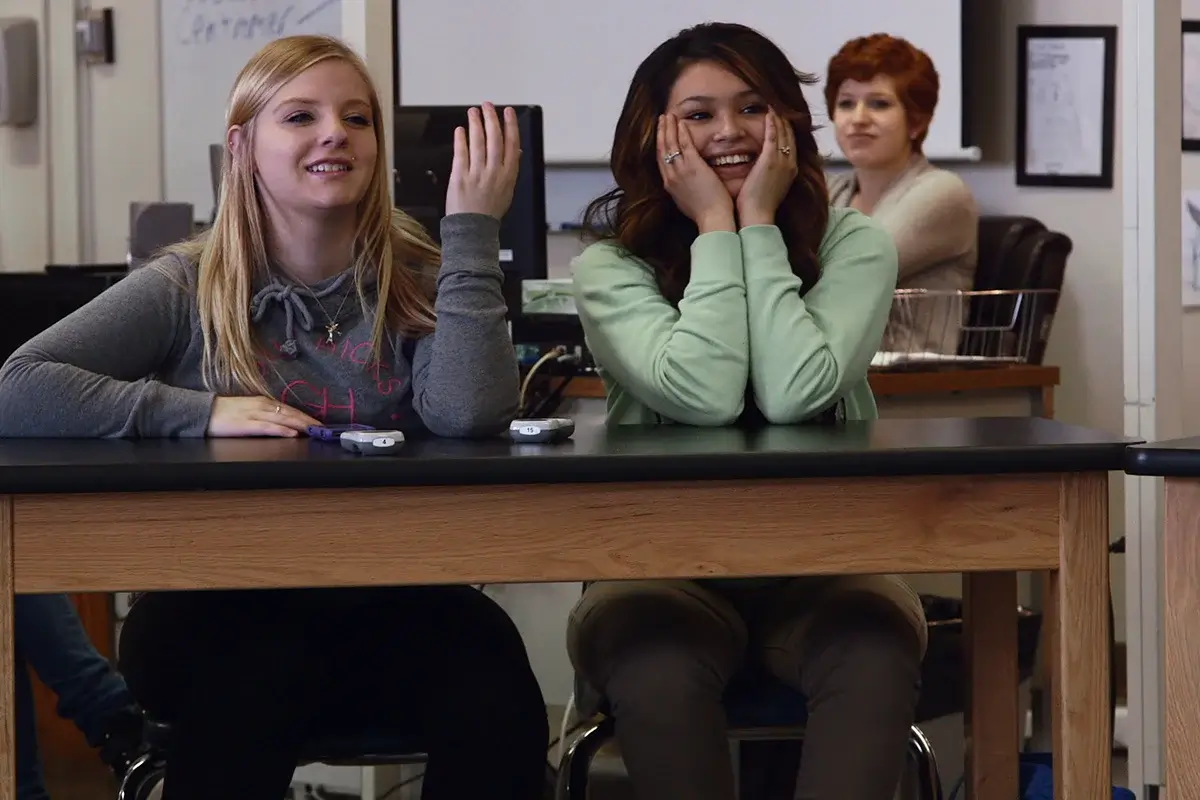

Image from "Paper Tigers"

It's this shift in perspective that produced a dramatic 85% drop in suspensions and a 40% decrease in expulsions, along with a notable improvement in academic performance and graduation rates.

Lincoln High School illustrates while trauma-informed practices and culturally responsive teaching are not cure-alls, they are powerful tools in the fight for educational equity.

Educators play a crucial role in this journey. As seen in "

America to Me," "

Paper Tigers," and similar documentaries, the impact of understanding and addressing the unique challenges faced by students can lead to transformative outcomes. In the face of daunting challenges, educators who prioritize equity and psychological safety are lighting the way to a brighter, more equitable future for all students.

As Sporleder says, "We'll never be able to reach 100% of the kids. But there's no reason we can't love 100% of the kids."

1. University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Education, "Diamond's new book examines, 'How Racial Inequality Thrives in Good Schools'," August 12, 2015. ↩

2. Nikki L. Aikens and Oscar A. Barbarin, "Socioeconomic Differences in Reading Trajectories: The Contribution of Family, Neighborhood, and School Contexts," Journal of Educational Psychology 100, no. 2 (May 2008). ↩