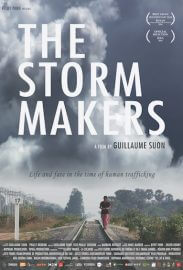

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/the-storm-makers

At the age of 16, Aya, a young Cambodian peasant, was sold into slavery by a “Storm Maker” – a human trafficker – who promised her a job as a maid in Malaysia. Now back in village, she is dishonoured and traumatised, and just as poor as when she left.

The unveiling of Aya’s fate, intertwined with the testimonies of human traffickers, offers an unsettling view of contemporary Cambodian society. By revealing the cruel exploitation of the rural population, the film raises an unsettling question: what is the price of a young peasant‘s life in Cambodia?

Featuring brutally candid testimony, The Storm Makers is a chilling exposé of Cambodia’s human trafficking underworld and an eye-opening look at the complex cycle of poverty, despair and greed that fuels this brutal modern slave trade. More than half a million Cambodians work abroad and a staggering third of these have been sold as slaves. Most are young women, held prisoner and forced to work in horrific conditions, sometimes as prostitutes, in Malaysia, Thailand and Taiwan.

The film tells its story from the perspectives of a former slave whose return home is greeted with bitterness and scorn by her mother; a successful trafficker — known in Cambodia as a “storm maker” for the havoc he and his cohorts wreak — who works with local recruiters to funnel a steady stream of poor and illiterate young people across borders; and a mother who has sold to the recruiter not only local girls, but also her own daughter.

At the age of 16, Aya was sold to work as a maid in Malaysia. She was exploited and beaten and eventually ran away, only to be captured and raped. When she returns home with an infant son, she is just as poor as when she left. Her mother greets her not with joy, but with anger that her daughter has come back with yet another mouth to feed instead of money. “I should have died over there,” says Aya in a singsong, childlike voice that masks the horrors she endured.

The young people from her remote village have migrated to work abroad. Empty houses are left behind. Cambodians call places like Aya’s village “ghost towns.” Suon and his assistant director, Phally Ngoeum, researched and filmed for three years, spending long periods in Cambodia’s villages and cities, and were able to gain the trust of both the victims and perpetrators of trafficking.

Pou Houy, 52, is a successful trafficker who runs a recruitment agency in Phnom Penh and claims to have sold more than 500 girls. Shockingly outspoken and shameless, he expresses no remorse and sees himself as a smart businessman, a good provider and even a good Christian. Although his company has been accused of trafficking by the local media, he has never been investigated by the police and continues to recruit young and poor Cambodians to work abroad.

Pou Houy’s enterprise relies on local recruiters, who bring him candidates from their rural communities. One of these is Ming Dy, who sold her own daughter and continues to supply Houy with new recruits from her village. She justifies her actions by claiming she has no other way to pay her bills.

In one wrenching scene, Ming Dy’s husband cannot bring himself to speak to his daughter when she calls from a new job abroad, where she earns a dollar a day. “I told my wife not to sell young people from the village,” he says. “Buddha condemns those who sell people like animals. I could have sold the bike and the oxen to pay back our debts. . . . But this money will bring us bad luck.” In another, a woman shows a picture of her 20-year-old daughter, who committed suicide in Cambodia after being trafficked. “She was so pretty,” says Ming Dy. The mother tearfully warns a new candidate for migration, “Don’t go abroad, girl!”

Pou Houy, the trafficker, supports not only his immediate family, but a dozen or so other relatives as well. His modern home, fancy car and concrete driveway contrast sharply with his relatives’ house right next door and its dirt road. But food is plentiful, and they are all better off than most people. “Does the trafficker feel regret?” asks Suon. “He was starving before, and made a promise to himself never to be poor again. From his point of view, in Cambodia you have only two choices: You are either a slave or a trafficker.”

How can a country descend into a state where trafficking family members and neighbors becomes acceptable? “Five or six years ago, during the financial crisis, a lot of factories shut down in Cambodia,” says Suon. “Hundreds of thousands lost their jobs and had to find a way to earn money. Trafficking networks took power because they were able to send thousands and thousands of people abroad — for them it was a golden opportunity, because people were starving.”

The film explores not only the political and economic roots of human trafficking but also the moral choices being made by those on both sides of the equation. Asks Suon: “Would you sell your neighbor or even your own child to a trafficking network in order to save your family? Which one of your children would you sacrifice? What becomes of your humanity once you decide to exploit another human being for profit?

“Cambodian migrants have been reduced to the status of slaves. They are transparent, or worse, completely invisible. I want migrants like Aya to feel free in front of the camera, allowing words to serve as therapy and an escape from the past.”

In September 2015, POV asked The Storm Makers filmmaker Guillaume Suon what’s happened since the cameras stopped rolling.

Where are Aya and her son now? Are you in touch with her and her family? Has anything changed in their lives or in their relationships with each other?

Since the completion of the film, Aya made the decision to leave her home and to work on construction sites far away from her village. She also decided that her son should stay with her parents, especially with her father, who feels guilty for what happened to Aya, and who still remains deeply wounded by this tragedy. He considers this baby as his own son now.

Aya needed time to accept this child. She was being violent with him shortly after coming back from Malaysia. But then, after a few months, her anger towards the baby disappeared. We talked with her about her relation with her son. She was first ashamed to talk about it. She understood full well that her son was not the one who hurt her, but said she couldn’t help it when the trauma of her experience was to difficult to bear.

We were deeply disturbed by this situation and talked about it with psychiatrists working with young women who become pregnant after rape. They told us that this situation happens in many cases — sometimes the mother abandons their child, or even kills them.

When we met Aya, she was already thinking about leaving her home, because the situation was unbearable for her regarding her relation to her own mother, and she wanted to distance herself from her son. We didn’t witness any violence against the baby. Working far from her home and being separated from her son helped Aya understand the violence of her behavior, and she started to accept her son.

We thought a lot about how to show this situation in the film. If one watches carefully, they’ll see she looks at the baby with a lot of intensity, as if she was trying to look for a way to love her child. The violence of her words covers these images to reflect the psychological complexity of her thoughts.

Before leaving him, she told us that she found in “his little black eyes the answers to her questions. He is just a baby. I will tell him later on that her father died. That’s all…”

And now she misses her son. She visits him as often as she can and suffers from being separated from him.

After the film, Aya fell in love with a young man who was working with her on a construction site. She got pregnant. Her boyfriend ran away, stealing her money, her clothes, her phone… Aya came back to us and we took care of her.

Aya is now living with her newly born baby girl and with her sister. She comes to us whenever she needs help, but she refuses to be taken care of by any NGO. She doesn’t trust any institution now. She wants to be free and to work to earn her living by herself, without depending on anyone. And we respect her decision.

Where have you screened the film? Can you share some of the responses and reactions that have been the most hopeful (or the most discouraging)?

The film has been broadcast on several TV stations, in Europe, the US and Asia, and it has been screened in dozens of film festivals around the world.

We received strong comments and reactions from viewers from Europe and the US regarding the last scene of the film, where Aya says that she kept the baby to hurt him.

Viewers thought that this scene was very painful to watch. For the majority of them, it acted as an eye opener on the situation for migrants. For others, it reflected their own incapacity to help migrants and haunted them for many days after they watched the film. Some others where angry, and wished they never have watched the film as it disturbed them deeply.

In Asia, this scene was seen from a different perspective. They seemed to be more aware of the ravages caused by human trafficking and lots of viewers explained to me that they themselves witnessed similar difficult situations for migrants and even told me that the situation in the field might be even worse for migrants.

Viewers have brought up the difficult question of whether you did — or should have — crossed the line between your role as a documentary filmmaker and as someone witnessing what could be an unsafe or desperate situation. How do you respond?

Lots of viewers asked me why I decided to make a painful film with no hope. It wasn’t a choice; the situation for the migrants is hopeless for the majority of them. I just translated what I witnessed in the field. My position as a filmmaker was to tell the story from the point of view of the migrants. I had to ask myself a question then: how can one expect to watch a film about human trafficking with a happy ending? What about the millions of migrants who suffer and die in horrific situations all over the world? What about those still locked up in prisons or in brothels? Shall I lie about the situation in order to make the film more watchable for the audience?

My role as a filmmaker is to be a “bridge between a situation I witnessed and the audience” — I am a kind of a translator, in a way. I wanted to give the opportunity to the audience to dive into the “reality of a person” from a short distance. My intention was to give the point of view from the inside. When the situation is as violent as the human trafficking system, the point of view itself is very violent.

Aya refused to work with NGOs, she refused to talked to journalists or doctors about what happened to her. I spent three years trying to reveal her testimony in a film so it could bring awareness about the global issue of human trafficking. I thought about the same mechanisms with the human traffickers who appear in the film. I positioned myself as a researcher who asks questions. Not as a doctor or a lawyer who tries to bring answers.

Of course I’m helping the people that I met in these villages, including those who needed help and who didn’t appeared in the film. But the film was not about me witnessing a horrific situation or trying to help them, but about the people who are really suffering alone in these villages.

It can be very dangerous to act as a humanitarian worker in these situations; one can bring more damages than help to those in needs. The film exists so it can help NGOs, politicians or lawyers who are fighting against human trafficking. And it can act as a trigger to the audience to ask, “How can I help to change this situation?”

Many viewers have requested information on how best to help Aya and her son, or others in similar situations. What organizations, NGOs or other avenues can viewers use to get involved? Are there any adoption agencies working to help at-risk Cambodian children?

• Tenaganita (Women’s Force)

• Licadho

• CHRAC

These three organizations are fighting actively in the field against human trafficking in Cambodia. They are working with international workers, field researchers and embassies to help the victims of trafficking.

The situation for adoption isn’t very straightforward in Cambodia and there have been abuses in the past, such as organizations selling children abroad or being involved in child prostitution.

I do hope that viewers will start to look around themselves, in their neighborhoods, and take actions on a local level first. How can a French or an American citizen help to fight against human trafficking in Cambodia? I don’t really know. But they can change the situation in their own country or in their own city for sure. This is where the fight against trafficking starts, and in every city, all over the world, one can find a victim of human trafficking. Countries like Cambodia are the point of departure for the migrants, countries like the US are the destination. All the countries in the world are part of the human trafficking system.

Hundreds of thousands of victims of human trafficking are living in the US, hundreds of thousands more in Europe and so on. There is a lack of organization to help these victims, a lack of shelter for them. Next to a viewer’s home, there is a local organization that needs help.

What conversations do you hope the public television broadcast of The Storm Makers will spark?

I hope that after watching the film, viewers will better understand the situation a migrant goes through before arriving in western countries. I hope they’ll think about what it is like for them back in their countries of origin and see these migrants with humanity. There are millions just like Aya all over the world, and I find it unbearable to see how they are treated when they arrive in western countries. I find it outrageous, the walls that are being constructed to push away these populations. I find it scandalous that we deport them back to their countries, back to their horrific situations, because we don’t want them next to us.

So the film is as violent as my anger, and my next films will be done in the same way. One of them is about the situation for migrants in western countries like France and the US.