Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

Enjoy a free preview via Film Discovery! Click here !

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/the-shelter

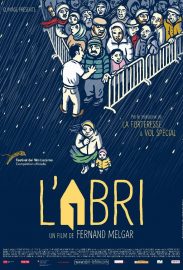

A winter spent in the heart of an emergency shelter for homeless people in Lausanne. At the entrance to this hidden bunker, each night the same dramatic ritual unfolds, leading to occasionally violent confrontations. The watchmen have the difficult task of “sorting the poor”: women and children first, men later if there is room. Even if the shelter can hold 100 people, only 50 “chosen ones” will be allowed inside to receive a hot meal and a bed. The others know that the night will be a long one.

Every night, against the most basic principles of human dignity, dozens of men, women and children are forced to sleep on the streets of my town. This happens every night, tonight, the night after tomorrow, it doesn’t stop. As I plunged into this hidden world of extreme poverty, it became clear to me that I would have to make this reality the subject of a film.

My encounters with workers from Spain, with Swiss work permits, at a local soup kitchen made me discover a new dimension of the flow of migration. They opened my eyes to the precarious population of foreign workers in Lausanne, largely composed of European economic migrants, trying to outrun the economic crisis and to find a job, a place to stay and a way to survive.

But poverty and exclusion have neither country nor ethnicity. The homeless population is heterogeneous, diverse and from all over. But what do we really know about these struggling people who try to stay in the shadows, silently roaming the streets at night in search of a place to sleep? Regularly turned away from crowded emergency shelters and chased out of public places, they are forced to hide to avoid police fines. The city of Lausanne has chosen to sweep these people under the rug and to sterilize its public spaces, as if poverty is a crime which threatens our well-being and stains our picture-perfect postcard landscapes.

Nobody has yet made visible the hidden life of these “undesired” workers. Apart from a few headlines, we know very little about their parallel universe, about their way of life and their survival networks, which we can only presume to be mysterious and difficult to discover. As the population of the excluded grows each day, silence and ignorance of their condition will continue to reign. Especially important in our current climate of xenophobia, I would like my film to help lift the veil on the existence and plight of these people.»

Because a municipal bylaw forbids “camping in a public space” (in other words, sleeping on the street), police patrols wake everyone found dozing on a bench, in a public park or at a bus stop, and order them to leave immediately.

Following a complaint, the police will regularly intervene in staircases, basements or car lots to throw out those who have found an improvised shelter. «We are in a tough spot» states Jean-Claude Nardin. «We suggest that the complainant install a door with a security code and we try to take the homeless person somewhere warmer. But it’s not easy; there are no free beds in the shelters. When it’s really cold, we give them a sleeping bag.»

Recently, after garbage was found and blame turned on the homeless, the last of the public places with heating have been locked up at night: underground parking lots, train waiting areas, etc. It has become almost impossible to find a warm place at night in the city of Lausanne.

MAROUÈNE, homeless, soccer player

«I sleep outside every night near Riponne with a dozen of fellow Tunisian compatriots. When it gets too cold you go into a public toilet. In Switzerland, we were the last ones to arrive so everybody thinks that it is all our fault. Before, it was the Italians and the Yugoslavs, and now the Arabs! We’re not all thieves, but we’re all put in the same box.

I’m desperately looking for work, but when a boss see you and knows that you are Tunisian, and in the morning newspaper he reads that a Tunisian stole this and that… of course he will not hire you. I’m angry at my countrymen who just do bullshit. Like when you see someone assaulting a 60-year old woman. This is not how we were raised. If I would see this I would immediately jump on him and break his face. Now we have no solution and I’m starting to do bullshit too. It’s impossible to get papers, impossible to find a job and impossible to return home. I call it the trap of Europe.

Before I was a soccer player. Since I’m living in Europe, I’ve changed. I smoke everything I can get cigarettes, hash, cocaine. It helps to forget. There is no hope for me here and at home… even less. There was hope for two hours after the fall of Ben Ali. Then we quickly realized it was going wrong. It’s even worse than before. You see all these guys with beards. You can’t drink anymore, you can’t kiss, you can’t do nothing. This is not what Islam is. This is not how I want to live.

We’re a lost generation. I hope that the next generation, 30 years from now, will live better than us. In Tunisia we treated well European tourists. We welcomed more than 10.000 Libyans escaping Gaddafi. And it’s a small country. And Switzerland, cannot accommodate 3.000 Tunisians?»

HOW MANY ARE THERE AND WHERE DO THEY COME FROM?

Lausanne’s social services believe that around 300 people found themselves homeless in the city last winter. The majority of them are single men, aged 20 to 50. Women, who make up less than a quarter of the homeless population, are most likely to be Romani and are often caring for their children.

A great majority of the African and Latino workers come from Spain and Italy. After benefiting from trade liberalization in the early 2000s, they were the first to be affected by the crisis that afflicts the countries of southern Europe. They have work papers, even passports, allowing them to travel and work in the Schengen zone. Many have a family to support, children in school and mortgages to pay. These are the working poor: their pittance of a salary doesn’t even allow them to have a roof over their heads.

Romani people have the right to travel in Switzerland but not permission to work. They must live, against their wishes, off of begging in the street. As Lausanne is one of the last cities in Switzerland to begging, their number there is constantly on the rise. They face strong reactions from the city’s citizens, who cannot stand to see such misery spreading on their streets.

North Africans, mostly from Tunisia, arrived after the Arab Spring. Young and full of hope, soon were frustrated by a lack of prospects. Aimless, some have fallen into addiction and delinquency. Usually when under the influence of drugs or alcohol, they can become disrespectful or violent when they are refused entry into one of the city’s shelters.

The Swiss are a minority because they benefit from strong mentoring and reintegration programs.

ALIOU & AMADOU, homeless, seller and farm worker

«We are Senegalese and we arrived together in Spain in 2006, we met on the boat. It was hard, but we worked and shared an apartment. We even got our European residence permit.

My friend Aliou comes from Dakar and he is the oldest son of the family. In Barcelona, he was a seller and made 1.700 EUR a month. Every month he sent money to his family. He was able to pay for the education of his sister.

I am Fulani and I come from the region of Saint-Louis. I am also the oldest of my brothers. First I left for Mauritania. There I had a shop and I lived well. By seeing so many people fleeing to Europe I decided to try my luck. I left to Spain and I worked in agriculture. I am very sorry because I earned more in Mauritania.

Because of the crisis in Spain, we lost our jobs, then our apartment. We decided to go North. We gathered the little money we had and we left for Switzerland because our permits allowed us to work in Schengen space. But here, we cannot find work and we don’t have any more money. Having only one meal a day at the soup kitchen, I lost 22 pounds. After our arrival, we sleep outside almost everyday. At night, it’s impossible to sleep more than 2 hours in a row, because it’s so cold.

The Police keeps checking us up on the street and awakes us up when we’re sleeping on a bench. We didn’t came to Switzerland to demand asylum, as we do not have political problems in our home country. Our problem is we don’t have any money. We are often proposed to sell drugs. It’s an easy way to get a bit of money. But we don’t want to do that. We don’t even know how to do it. We always won our money honestly. It’s getting harder and harder everyday.

We’re stuck here. We can’t go back home with empty pockets. Our family is counting on us. In Senegal, there is no future, everything is blocked. But where there’s money there is always hope. Here there is money. If it doesn’t work here, we leave for Germany.»

THE EMMERGENCY LODGING CENTRES

It was during the winter of 1992 that the city of Lausanne opened its first overnight welcome centre, to serve the city’s growing homeless population. The city of Lausanne developed two overnight emergency shelters, with the intent of forming a safety net which would allow the local precarious population to find a temporary lodging solution. The city’s message is clear: “Not a single Lausanne citizen should have to sleep outside!”.

These shelters were meant to offer a safety net to citizens finding themselves on the street, before they could be taken care of more comprehensively by social services.

After a person was found frozen dead on the street in 2001, the city opened a third seasonal emergency structure called The Shelter. The three shelters in Lausanne, with a combined total of 55 beds in summer and 119 beds in the winter, are now always filled. The number of homeless persons, however, has not stopped increasing. In 2011 there were 26 224 registered overnight stays and 8 767 refusals.