https://www.filmplatform.net/product/crumb

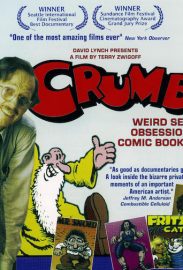

Presented by David Lynch, Terry Zwigoff’s film Crumb is a sometimes hilariously funny but often disturbing journey into the mysterious and creepy world of underground artist Robert Crumb and his brilliant, talented but deeply dysfunctional family; his recluse mother and his two brothers (both artists), Charles and Maxon. Crumb’s twisted, violent and at times even outright pornographic cartoons are witnesses of his utter disgust of the American society and culture and made him world-famous in the 60’s when he created Mr. Natural, Fritz the Cat, the Keep On Truckin’ cartoons and record sleeves for musicians like Janis Joplin.

Crumb is best known for three pieces of work. The first is his drawing, “Keep on Truckin'” which has adorned everything from mud flaps to coffee mugs. The second is his cover art for the Big Brother and the Holding Company (featuring Janis Joplin) lp, “Cheap Thrills” and the third is the adaptation of his randy character “Fritz the Cat” into a feature animated film by Ralph Bakshi. Since the early underground comic days (the first Zap comic appeared in 1968), Crumb has produced an enormous body of work and his comic work is more widely read today than ever. Critics have come to recognize him as an extraordinary talent, and his work is now finding its way into museums.

Robert Crumb is a cult hero, an artist whose work is collected as fine art, and an iconoclast, a spokesperson for those who began questioning authority in the 1960’s.

Anyone familiar with his work knows that Crumb is as searing a social critic as anyone working today. Crumb’s acute eye and ear render the familiar, painfully funny circumstances of life’s rich pageant with scintillating precision. As Robert Hughes comments, “… you come away from Crumb’s work with the feeling that you’ve seen some part of human desires, fantasies, actions, aggressions, which are all actually very truthful about the way we fantasize, dream and act toward one another.”

Crumb’s finely-honed skills as a social critic were born out of a youth spent in a twisted rendition of the American dream. In fact, the film is in many ways the story of the Crumb family; a family that created three artists – brothers Charles, Robert and Max – one of whom became famous. Crumb’s family life set the tone for the art that followed. Crumb has said: “As a teenager, there was no place where I fit in at all. I saw no hope of ever connecting with anything. The instant I realized I was an outcast, I became a critic. I’ve been disgusted with American culture from the time I was a kid.”

The painful honesty of Crumb’s work is also manifest in the artist’s extreme interest in the subject of sex. As Crumb states in the film: “When I was five or six I was sexually attracted to Bugs Bunny. I cut out this Bugs Bunny from the cover of a comic book and carrier it around with me. I’d take it out and look at it periodically and it got all wrinkled up from handling it so much that I asked my mother to iron it.”

Crumb’s work on women and sex reflects a completely frank and unfiltered take on the subject – in effect, a voyage through the male psyche with an id tour guide. But the more deep seated questions raised by his probing of male-female relations are often very disturbing, considered objectionable by some and obscene by others.

Crumb is a portrait of an artist who has spent his life swimming against the tide. Its style, like that of its subject, is frank, intimate and darkly humorous, full of disturbing revelations about the less-than-sane world we all live in.

Upon viewing the completed version of this film, cartoonist Robert Crumb, whose story it tells, informed director Terry Zwigoff, “After I saw it I had to go for a walk in the woods, just to clear my head. I took my favorite hat off, this hat that I’ve had for 25 years, and I threw it off a cliff. I don’t want to be R. Crumb anymore.” Considering the material, the reaction is understandable. This is the sort of movie capable of prompting a viewer to question and evaluate a great deal more than the inner workings of a single man. In addition to presenting one of the most compelling filmed documentary character studies of all time, Crumb asks a lot of pointed questions about life and art that no one can possibly answer, least of all the misanthropic genius at the center of the portrait.

“My work is full of sweating, nervous uneasiness, which is a big part of me and everybody else,” says Crumb. “Most people don’t want to see that though, because it reminds them of inadequate parts of themselves.” Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects for any viewer of Crumb is to identify elements of their own personality reflected in what Zwigoff uncovers. Crumb doesn’t tone down his often-bizarre opinions just because the camera is on.

Crumb’s claim to fame is founding the underground comics movement in 1967, when issue #1 of his “Zap Comix” was released. Crumb is also the creator of the “Keep on Truckin'” logo, the artist for the LP cover of Big Brother and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills, and the originator of Fritz the Cat, which Ralph Bakshi turned into the first X-rated animated feature (a film that Crumb hates). Crumb, made with even-handed passion by Zwigoff, does not attempt to be a complete chronicle of the cartoonist’s life. Instead, the movie chooses to examine certain facets of his personality, his and others’ impressions of his work, and the forces which contributed to the genesis of a product that has been called everything from satirical genius to pornographic filth.

Through interviews with Robert Crumb, his brothers Charles and Max, his current wife and ex-wife, his son Jesse, and various art critics, Zwigoff constructs a Picasso-like image of the man and the influences underlying his creativity. One of the most important of these is surely the dysfunctional family environment of his childhood. With a father labeled by Charles as an “overbearing tyrant” and “sadistic bully”, and a mother who became an amphetamine addict, it’s no wonder that Crumb is filled with anger, disgust, and hate. But, as deep as his bitterness runs, the artist possesses a streak of sardonic, self-deprecating humor that shines through. At one point, Crumb states, “At least I hate myself as much as I hate anybody else.” In fact, in omparison to his two brothers, Crumb appears almost normal. Charles is a manic depressive who takes medication to keep suicidal bouts at bay (one year following Zwigoff’s Philadelphia interview, Charles killed himself). Max, a confessed sex offender, spends several hours a day meditating on a bed of nails.

Is Crumb a misogynist? Probably, since, in his own words, he harbors inner hostility towards women. But there’s more than that to his work. Time magazine art critic Robert Hughes defends Crumb, saying that his work expresses fantasies that are common, but which most of us repress out of fear. Mother Jones editor Deidre English has a different view, indicating that Crumb’s fetish for depicting overendowed, headless female bodies is a manifestation of his “arrested juvenile vision.” It’s even suggested that putting such fantasies on paper is “dangerous.” Zwigoff gives both sides of the argument equal time, and never editorializes. It’s up to the viewer to decided which position, if either, he or she accepts.

Is Crumb obsessed with sex? No doubt. Apparently, there was a time when he masturbated four to five times each day, and everyone seems to agree that he finds his own work sexually stimulating. The cartoonist’s views of sex may not be of the “normal” variety (just ask one of his ex-lovers), but he definitely enjoys certain activities.

Is Crumb disgusted with popular culture and fame? In his own words, “As a teenager…I realized I was an outcast, I became a critic, and I’ve been disgusted with American culture from the time I was a kid. I started out by rejecting all the things that the people who rejected me liked, then over the years I developed a deeper analysis of these things.” Crumb has turned down opportunities to make hundreds of thousands of dollars by going mainstream. He will not sign autographs. And he rejects the romantic notion of love, saying the only woman he has ever loved is his daughter.

Whatever opinion a viewer has of Crumb at the end of this film, an apathetic reaction is unthinkable. Empathy, fascination, disgust, or anger are all likely, but not disinterest. R. Crumb is the sort of person it’s impossible to ignore, and Zwigoff’s film creates such an honest portrayal of him that some sort of response is demanded. Crumb is a rare and powerful documentary that completely absorbs the viewer and leaves an impression so blindingly clear that the afterimage cannot be blinked away even when the theater is far behind. Crumb and his words will tug at the mind with all the tenacity of a pit bull tearing at its prey.

© 1995 James Berardinelli

CRUMB was on over 100 critic’s lists of the TEN BEST FILMS of 1995 even

though it was a documentary. It was named BEST FILM of 1995 by a dozen major film critics including Gene Siskel, “Siskel and Ebert” ( named 2nd Best by Ebert); Andrew Sarris (New York Observer)called it : “One of the most amazing films ever made!” Premiere Magazine’s annual critic’s poll named it the Best Film of 1995. Entertainment Weekly Magazine’s annual critic’s poll also named it the Best Film of 1995. Jonathan Rosenbaum (Chicago Reader) : “A Masterpiece!”

It won the award for Best Documentary of the Year (1995) prize from the

following:

Sundance Grand Jury Prize

DGA (best director)

National Society of Film Critics Association

New York Film Critics Association

Los Angeles Film Critics Association

Chicago Film Critics Association

Boston Film Critics Association

National Board of Review

National Broadcast Film Critics Association

International Documentary Association

Terry Zwigoff also directed the critically acclaimed 1985 documentary

“Louie Bluie” and will have his first feature “Ghost World” released this

year by United Artists/MGM.