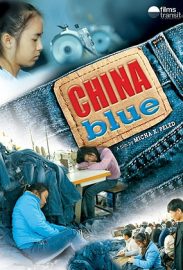

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/china-blue

China Blue takes us inside a blue-jeans factory, where two teenage girls, Jasmine and Orchid, are trying to survive the harsh working environment. Their lives intersect that of the film’s other protagonist and factory owner, Mr. Lam. Providing perspectives from both the top and bottom levels of the factory’s hierarchy, this film brings complex issues of globalization to the human level. Like millions before her, Jasmine leaves her home village for a far-away factory job. Her initial excitement to be able to help her family quickly melts away as she is overwhelmed by the long work hours and the delays in pay.

More on Film

I made this film because I believe globalization is the most important issue of our times. What gets me up in the morning is my outrage. Multinational corporations with care for nothing but the bottom line are controlling more and more of our lives. Dominating the media, they ensure that serious examination of their actions rarely takes place. For me, the only appropriate response is to make films that expose what they don’t want us to see.

My previous documentary, Store Wars, followed what happens to a small town when a Wal-Mart megastore arrives. Now I wanted to make a film about the other end of the same thread — how retailers like Wal-Mart acquire their cheap goods. I also wanted to explore our complicity as consumers in causing havoc, not only to our lives but to those on the other side of planet. I think of China Blue as a prequel to Store Wars.

To make this film, we had to overcome many obstacles. As the world’s largest producer of consumer goods, China was the obvious location for this globalization story. But China requires a film permit and then attaches a government official to oversee the production. To avoid such control we smuggled in our equipment. The police stopped us numerous times, arrested my crew and confiscated our tapes. Our main character, a 16-years-old girl, was intimidated and we had to start filming all over again with a new protagonist. Labor organizing is also illegal in China. We had to work with an underground network of labor activists who risked their liberty to help us. They want the world will know how China’s workers are being exploited.

Still, the terrible sweatshop conditions are created not by the government, but the multinational big brand retailers. They pressure the factories to keep their cost inhumanely low and their production all night long. They demand such low prices that the factories can remain competitive only by violating China’s labor laws that guarantee minimum wage, overtime compensation and rest days.

The retail companies tell us that if workers were paid better the price of our consumer goods would go up. This sounds reasonable – until you see in the film that the workers who make your jeans are paid $1 – all of them together. In other words, the labor cost makes up only 2%-3% of the retail price. Even if salaries were doubled it should have very little impact on the price. Most of what we pay stays with the retailers, who charge us ten times the cost of making the goods.

These are the same companies whose websites promise social responsibility and decent labor standards. To maintain the charade they require the factories to prohibit all media access. And for a good reason. Once you have seen China Blue and got to know Jasmine and Orchid, the people who make your clothes are no longer faceless strangers.

THE MAKING OF

Like no other film before it, Micha X. Peled’s CHINA BLUE is a powerful and poignant journey into the harsh world of sweatshop workers in China. Shot clandestinely in ,China under severe conditions, this is a deep-access account of what both China and the international retail companies don’t want us to see–how the clothes we buy are actually made.

For Jasmine, a thread-cutter in a blue-jeans factory, the working conditions she and her friends endure are literally unlawful by Western standards, and tensions in the factory are already running high. So when the factory owner strikes a deal with a Western client and demands around-the-clock production in order to meet the deadline, a confrontation becomes inevitable.

Shot Clandestinely

China maintains tight control over all foreign media. Filmmakers from abroad are required to obtain permits to film. If permission is granted, officials from the Propaganda Department accompany the production unit from the moment they arrive and are present throughout the filming. For obvious reasons, we chose not to apply for such a restrictive permit.

Instead, we smuggled our DV camera into China by disassembling it and stashing the various parts into separate shopping bags. The bags were then carried across the Hong Kong-China border by a woman who simply blended in with the usual flow of daytime shoppers. As well, we openly carried a mini-DV camera as many tourists do.

Getting the equipment into the country, however, was only the first challenge. When we left the safe confines of the factory –where most of the filming took place — to follow our characters back to their home villages, trouble found us yet again. In the countryside of Sichuan province, even our small crew stood out. Though we hired local cameramen to film, the production was nonetheless halted by police time and again.

The first police intervention occurred while we were filming… a love story. On the occasion of her 20th birthday, Orchid, a zipper installer at the factory, returned home after a 2-year absence to introduce her boyfriend to her family. Up to that point, Orchid’s parents had not approved of her partner; they had never met him, but he was from one of the poorer families in the village. The day before the boyfriend’s arrival the police caught up with us. They threatened to have the cameraman fired from his regular job at a local TV station, and ordered us to leave the area at once. The crucial moment in Orchid’s love story – -which we had followed for six months – -was about to be missed.

Undaunted, we went only as far as Louzo, the nearest city. We hired a driver whose truck had tinted windows and returned to Orchid’s house early the next morning. The house was located on a remote hill outside the village and was accessible only by foot. We took the road as far as it allowed, then lugged the equipment up the hill and through a bamboo forest. We filmed Orchid’s birthday party ourselves, but we were unable to understand any of the conversations since Orchid and her family spoke a Sichuan dialect we did not understand.

On yet another occasion, the police prevented us from filming a factory strike. Thanks to our production coordinator, a Hong Kong based CNN stringer who intervened on our behalf, we escaped arrest.

The most trying event, however, took place the following year. After an eight-month lull in filming due to SARS, we returned to China to find that Little Fish – -our original main protagonist, had quit her factory job and returned to her village. We arranged to film her at home, and again hired a local cameraman. This time director Micha Peled – -the only Western-looking person in the crew — remained in a town an hour away. Still the police intervened, arresting not only the cameraman, but our Associate Producer Song Chen as well. When the police learned that Chen was a Taiwan-born U.S. citizen and not Chinese, they subjected her and the cameraman to an all-night interrogation. It took frantic calls to various contacts before the police finally let them go, but the tapes were confiscated. Subsequent attempts by the U.S Consul to have the tapes released proved futile. By this time, Little Fish was no longer interested in co-operating, and we had to return to the factory and start filming all over again with a new protagonist — Jasmine – -who had just arrived seeking a job. As a result, all the scenes with Little Fish were removed from the film.

Getting Inside

Like some of Micha X. Peled’s previous films (Store Wars, Inside God’s Bunker), China Blue is primarily a deep-access film. It is the first documentary to penetrate so completely the inside workings of a sweatshop factory, capturing scenes not only on the factory floor and in worker dorms, but also at management meetings and during tense negotiations with Western buyers.

The main challenge for us was to get a Chinese factory owner to allow us to film. Naturally, most factories declined to have an unsupervised camera crew prowl their premises at all hours as Peled requested.

After knocking on many doors our luck finally changed when we met Guo Xi Lam, the owner of a jeans factory in Shaxi. The town’s former police chief turned-businessman, Mr. Lam was proud of his newly built factory. He was flattered to be considered for an American film, which he believed was about the first generation of China’s entrepreneurs. Mr. Lam instructed everyone in the factory to co-operate with us at all hours.

To select a cast for the film among the hundreds of workers at the factory, Song Chen moved into the compound and lived with the workers. As in all export factories, the workers sleep in dormitories located inside the factory’s compound. Chen was given a bunk in a girls dorm room where she was able to form close bonds with a number of workers. We cast the film based on the profiles Chen e-mailed back to Peled. Production, however, took much longer than anticipated – -interruptions ranged from SARS to police intervention and confiscation of footage. To ensure Mr. Lam’s continued co-operation we cut for him, out of the documentary footage, a sales promo DVD featuring happy workers who were proud to work around the clock to meet all deadlines.