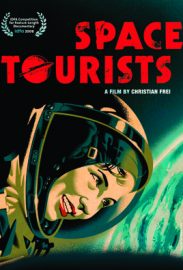

Forty years on from Neil Armstrong’s ‘one small step for man’, we are still waiting for the ‘giant leap for mankind’. Space travel, once the most fiercely contested race of the cold war era, has slowed to a crawl. Two decades after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Swiss documentarian Christian Frei (“War Photographer”, “The Giant Buddhas”) takes a laconic, humorous look at the way billionaires depart our planet earth to travel into outer space for fun. Focusing on four main stories, Frei’s film travels to three far-flung corners of the world – and soars 250 miles above it. Norwegian-born Magnum photographer Jonas Bendiksen introduces us to the bizarre poetry of the abandoned Kazakh city of Baikonur, the main launch site for the Soviet space programme. Once home to 100,000 people with even its children’s playgrounds space-themed, Baikonur maintains a skeletal staff and enough facilities to carry out a launch – when there is the money to pay for it. Enter Anousheh Ansari, the first female space tourist. Ansari is an Iranian-born American millionaire who dreamed as a child of going into space, and now has the funds to make her dream a reality. We follow her through training, launch, orbit (where she experiences days of accelerated sunrise and sunset, the zero-gravity toilet and the problems of washing your hair in a weightless environment), right up to her return to earth, where she is handed a bunch of red roses and bites into a fresh, juicy apple. Meanwhile, a few hundred miles north from where Anousheh blasts off, a ragtag band of scrap-metal merchants set off in their trucks for the spot where the first stage of the rocket will fall back to earth, providing rich pickings from its valuable metals. These will eventually be sold to China, where they are likely to be converted into aluminium foil of the kind used to wrap sandwiches. The scrap dealers enthusiastically agree that nothing is quite like beshbarmak (Kazakh lamb stew) cooked in the open air – especially when the cooking pot is a retrieved rocket part. And several hundred miles further north again, where the next stage of the rocket falls into a more populous area, farmers use the junk to mend houses and make tools, oblivious to the potential chemical hazards. Next, thousands of miles away in Romania, we meet Dumitru Popescu, a participant in an initiative set up by Ansari (and subsequently backed by Google) to reward the first private individual to send a vehicle to the moon. A low-tech scheme even by Baikonur standards, Popescu’s idea – helped on by screwdriver and hammer – is to float his prototype up into the stratosphere on a giant Montgolfier balloon before igniting the rocket. Inflation of the balloon goes according to plan. But that’s about as far as it goes. “At least it’s flying somewhere,” mutters Popescu, as his precious rocket bounces toward the Black Sea, still convinced what he is doing is anchored in the development of a modern business plan, not the fulfilment of a childhood dream. Meanwhile, back in mother Russia, another wealthy space tourist – Charles Simonyi, Chief Architect of Microsoft’s Word and Excel programmes – bicycles through the still heavily guarded ‘Star City’, where Soviet cosmonauts once trained. For Simonyi, preparation for the dream is a matter of physical tests, training and space-menu sampling. The space-kitchen staff, direct descendants of the floor ladies who used to control Soviet-era hotels, sternly ply Simonyi with a variety of tinned foods, duly noting his opinion of ‘Perch in Jelly’, ‘Pork with Buckwheat’, ‘Zucchini Caviar’… Frei’s skill as an observer obviates the need for verbal commentary or even insistent editing. Like all good documentarians, he gets reality to do his job for him. The wonderfully do-it-yourself nature of Dumitru Popescu’s rocket, ingenious in its design but clumsy in its construction, is embodied in the shot of a tag-along dog sleeping comfortably in its shade. The fascinating ordinariness of the Russian space programme has none of the carefully choreographed drama that we are familiar with from the Americans at the Kennedy Space Center.The Soyuz-Rocket trundles to its launch-pad towed by en elderly locomotive amid minimum security. Ansari rides up the gantry in an industrial elevator. Then, as we observe the Russian rocket exuding clouds of liquid oxygen in the middle of what appears to be an empty steppe, a voice simply asks ‘Ready?’, like a parent about to let go of a child riding a two-wheeler for the first time without stabilisers. In the end, the everyday takes over from the aspirational, with man’s journey beyond the final frontier becoming just another border for tourists to cross in search of something new, while a shepherd uses part of a space rocket that fell from the sky to complete his humble yurt. The film opens with a quote from Arseny Tarkovsky (father of the film-maker), which sums up how Russians once felt as they stood at the threshold of space: ‘Here I am at the centre of the world. Behind me myriads of protozoa, before me myriads of stars’. The same lines, again inviting awe, are repeated in the middle. But the concluding part of the quote does not come until the end credits, bringing the heroic back to a more human scale: ‘A little butterfly, a thread of golden silk, laughs at me like a little child’. Nick Roddick