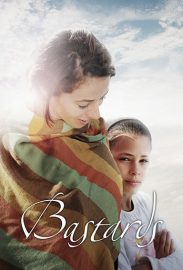

https://www.filmplatform.net/product/bastards

In Morocco, as in all Muslim countries, sex outside marriage is illegal. Single mothers are despised, but what is the fate of their children? They are outcasts, condemned to a life of discrimination. Bastards is the first film to tell this story from a mother’s point of view. We follow Rabha El Haimer through the courts to legalize her forced marriage, to register her daughter and to make the father accept his child.

Deborah Perkin captures real life courtroom drama, played out in the first Muslim country in the world to recognize that single mothers and illegitimate children have human rights.

The director answers some FAQs:

Why did you make this film?

Rabha is a remarkable character, an illiterate child bride with no legal rights, who fights back to claim a better future for herself and her daughter. I desperately want the world to see her story, to admire her battle for justice and to celebrate her success. I found her story through my passion to tell a good news story from the Muslim world.

I am sick and tired of seeing negative media stories about Muslims as male terrorists and female veiled victims. I want to look behind the stereotypes, to explore the ordinary lives of Muslim people. Bastardslooks candidly at sex, love, parenthood and money – the universal themes that concern us all.

So where did you start?

I went on holiday to Morocco with my mother! We were impressed with the way women seemed to be engaged in society, more than in other Muslim countries we had visited, though we didn’t claim to be any sort of experts. When I got home I discovered that Moroccan family law reforms of 2004 gave women a measure of equality. The position of single mothers and illegitimate children is slowly changing for the better. Even though many Moroccans think the reforms don’t go far enough, it seemed like a very unusual step in the right direction. So I started talking to Moroccan lawyers, and searching for a documentary subject which could show the law in action.

How did you find out about the plight of “bastards” in Morocco?

In my search for a subject I quickly came across Aicha Chenna’s pioneering work for single mothers. She’s a national heroine in Morocco, and increasingly around the world. The French government has recently awarded her their highest honour, the Legion d’Honneur and previously she won the American Opus Prize celebrating religion in social action. She’s determined that children shouldn’t suffer because their parents aren’t married, and wants them to be full members of Moroccan society. Her charity L’Association Solidarite Feminine advises single mothers how to use the law to their advantage. Over 50 years, Aicha Chenna battled religious and social prejudice and helped to reform the law. Compared with the West, the rights of Moroccan single mothers may be very narrow, but compared with other Muslim countries, they are amazingly broad. No woman is jailed or executed for breaking the family law.

How difficult was it to gain access to film the lives of these women and their children?

In any observational documentary, first of all you have to win people’s trust. Why should a charity like L’Association Solidarite Feminine open its casebook to a British filmmaker without a lot of discussion first? We came to an agreement over the course of a year, shooting a taster tape, and discussing the ground rules. Crucially, I had to agree to hide the identities for the Moroccan audience, of any single mothers who preferred to remain anonymous. One of the women in the film lives in fear for her life, believing that her father would kill her if he discovered she had had an illegitimate child, so her identity is hidden for all viewers around the world.

The long negotiation and preparation over, and the agreement with the charity in place, I had the most wonderful welcome from the single mothers themselves. I had expected nine out of ten single mothers to be camera-shy, but the opposite was true. Very few women refused to be filmed and most wanted to tell me their stories and laugh and cry with me. It was a privilege to be allowed into their lives, and they seemed to enjoy the confessional nature of documentary making. My Assistant Producer Nora Fakim speaks Arabic, and I don’t, but it’s amazing how much communication can take place non-verbally. I think it also helped that Nora and I lived in a slummy part of Casablanca where the single mums live, and word got round that we were sharing a room, sleeping on two mattresses, in a house without a bathroom, cooking on a stove in the corridor and using the local hammam. We certainly didn’t come across as pampered media types.

Why should non-Muslims care?

We are all human beings, living in a global village and we should take an interest in each other, and help where we can. Having said that, this isn’t a film that people “ought” to watch because it’s politically correct. Quite the opposite! It’s closer to being a gritty courtroom drama, or a soap opera, with women and men talking frankly about sex, money and marriage. It’s the stuff of everyone’s lives. And it’s not so long ago that illegitimate children were stigmatised in the West.