In the world of research, the pursuit of knowledge can lead down many paths. Great works are often evolutionary, molting, merging, or changing into something unlike where they started.

It’s something academic researchers and documentary filmmakers have in common, and you’ll find at the intersection of these two fields: the convergence of analysis, truth, and narrative.

Whether delving into historical archives or contemporary social issues, academics can find a powerful ally in documentaries—a medium that transforms data into stories and brings to life complex concepts through lived experience.

Many documentarians are researchers themselves, having gotten their spark of inspiration in the dark corners of university archives or from researching another topic that revealed a new rabbit hole to investigate.

Exploring this dynamic interplay reveals the potential of documentaries to inspire new research, provide rich empirical viewpoints, or bring academic findings to life in a way that engages and informs both the scholarly community and the wider public.

Rona Sela, a lecturer and researcher of visual history at Tel Aviv University, first began her search into Palestine’s visual history over twenty-five years ago. Sela was hoping to uncover photographs of Palestinian life before the state of Israel was established, but her investigation instead led her to discover decades of pre-Israel, Palestinian cultural archives stolen during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in the 1980s - and kept under lock and key ever since.

In

a 2018 essay, she notes, "These colonial rules and regulations embodied in the work of Israeli colonial military archives are not only imposed on plundered archives but also on material of Palestinian importance produced by Jews/Israelis charting colonialism. This is because they too have the potential to crack the colonizer’s narrative."

1

The discovery led to a change in career trajectory from academic to filmmaker. As a result, the documentary “

Looted and Hidden–Palestinian Archives in Israel” was created to bring these suppressed materials to the public and further examine the way their concealment shaped cultural identity, history, and politics for decades.

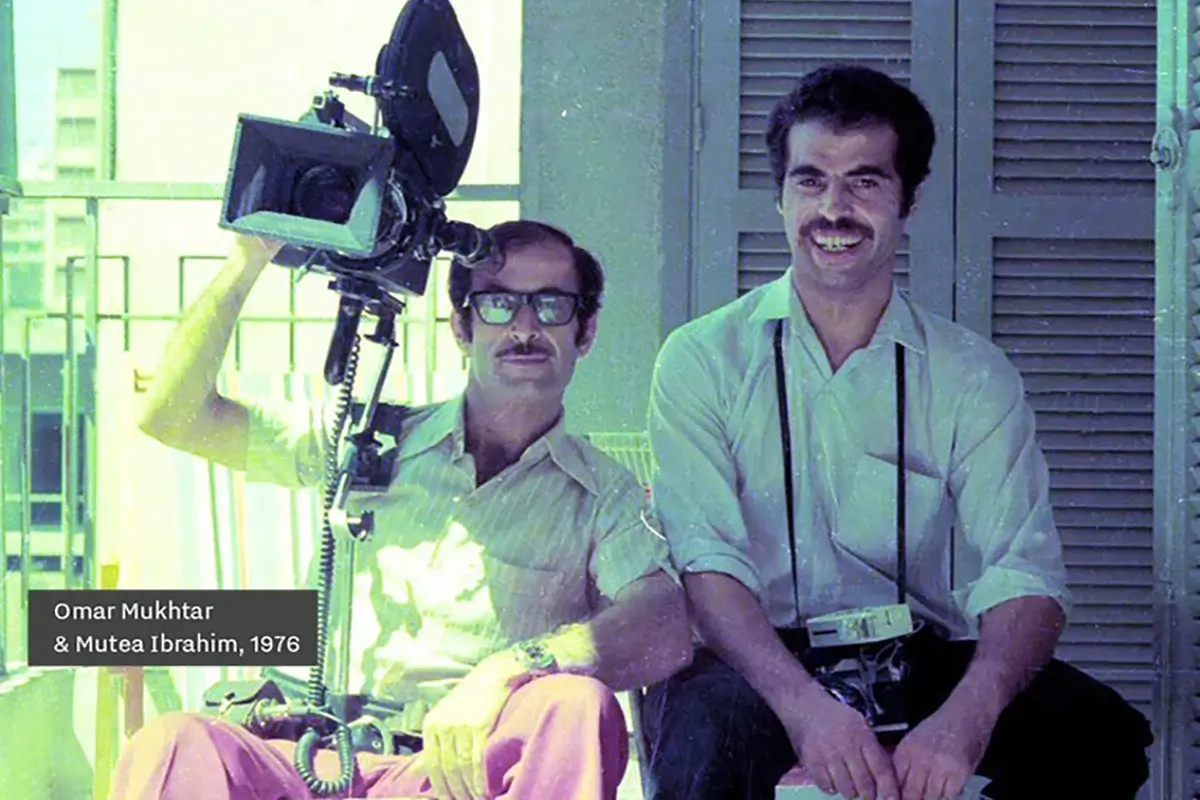

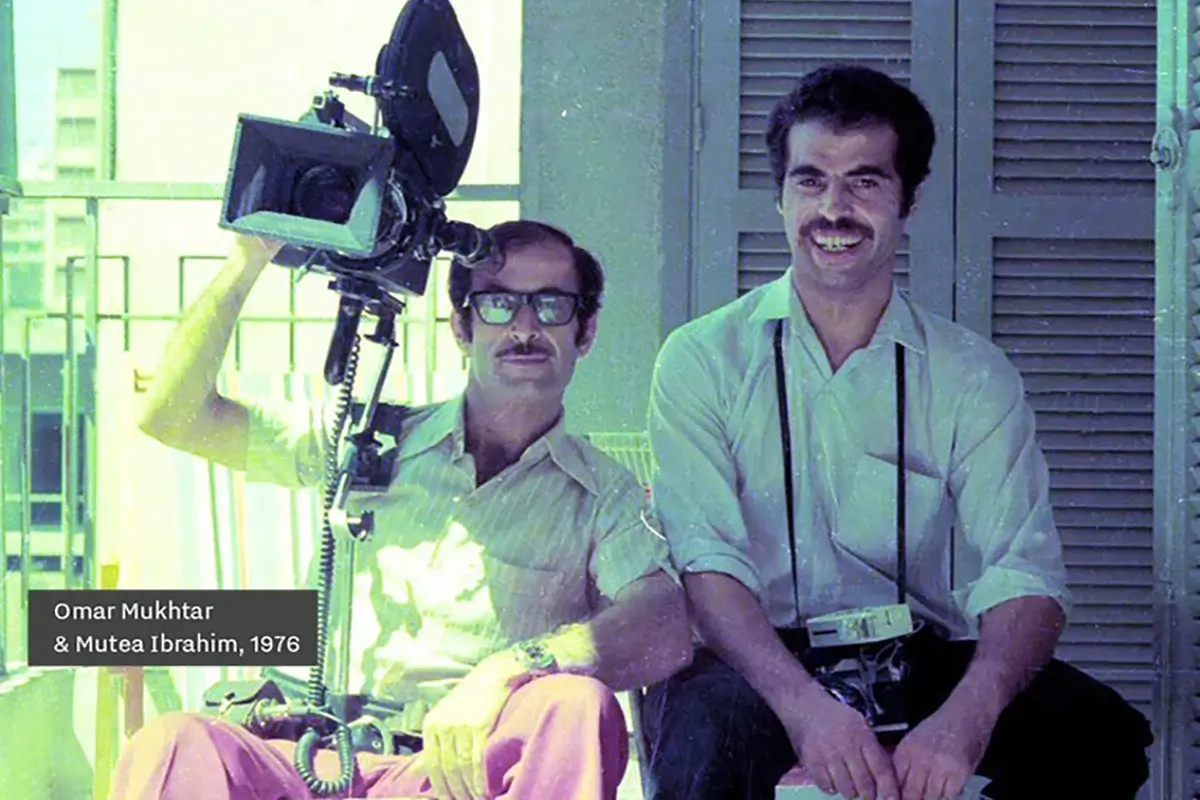

Image from "Looted and Hidden–Palestinian Archives in Israel"

In a

2017 interview with Al Jazeera, Sela emphasizes, "As a researcher of visual history, I understand the importance of visual images and archives in constructing self and national consciousness and identity and the importance of culture and history to its society."

Through "

Looted and Hidden," Sela not only unveils these concealed histories but contextualizes the complex social and political power dynamics constructed in colonization.

While academic research has birthed some of the most compelling documentaries, the reverse holds equally true—documentaries can also serve as catalysts toward new scholarly pursuits.

Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 film, "

The Act of Killing", examines genocide denial and the psychological effects of war in the long shadow of the 1965-1966 Indonesian genocide. In the experimental documentary, Oppenheimer follows executioner Anwar Congo and other former death squad leaders responsible for the mass killings of alleged communists, minority groups, and political opponents during that period.

The film takes a unique approach, inviting the perpetrators to reenact their crimes in the style of their favorite film genres, including westerns, gangster films, and musicals. Through this process, the film delves into the psychology of the killers, their lack of remorse, and the societal structures that have allowed them to remain in positions of power and influence decades after the atrocities.

Image from "The Act of Killing"

Oppenheimer spent eight years embedded with a group of survivors of the genocide to better understand the current-day regime and the pervasive fear that remained from a genocide that was no longer acknowledged. He spent another two years talking to perpetrators to bring them on board for the project.

What "

The Act of Killing" achieves best is not its visualization of history, but in connecting history to the context of today. As Oppenheimer wrote in a 2014 article for

The Guardian, "The film is not a historical narrative. It is a film about history itself, about the lies victors tell to justify their actions, and the effects of those lies; about an unresolved traumatic past that continues to haunt the present."

The documentary caused a stir, both in Indonesia and abroad, as it forced a national response and a global review of the effects of genocide and war.

It has inspired countless academics to respond, formulate analysis, theories and observations on human psychology, international politics, journalism, film and more.

In her book,

Memory Unbound: Tracing the Dynamics of Memory Studies, Australian National University Professor Rosanne Kennedy, argues that the film provides "an opportunity to explore the transcultural limitations of Holocaust memory as a paradigm for remembering other genocides."

2

The film has also served as a touchstone for other notable academics who have referenced the film in research on psychology, international politics, and history. The film's unflinching look at the psychology of perpetrators has provoked a reckoning with the legacy of genocide and the complex interplay of trauma, power, and denial. Academics have seized on the documentary as a springboard for new research agendas and theoretical frameworks.

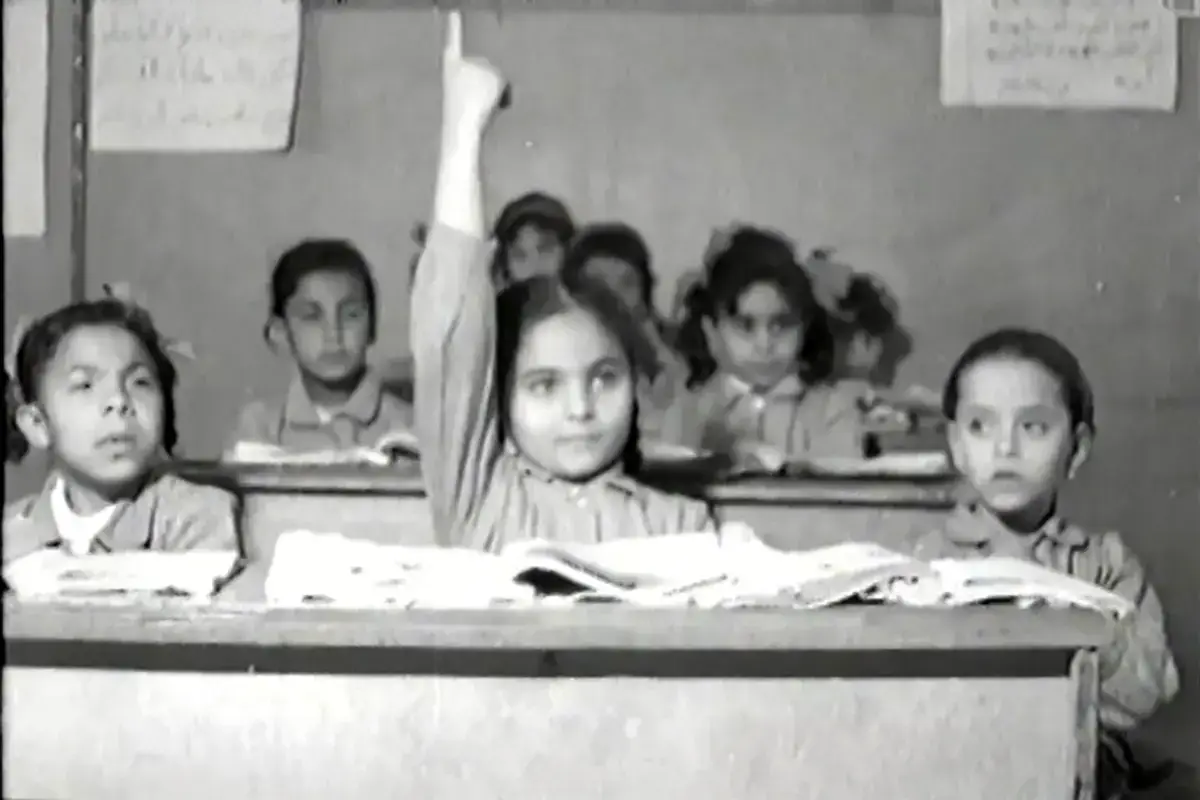

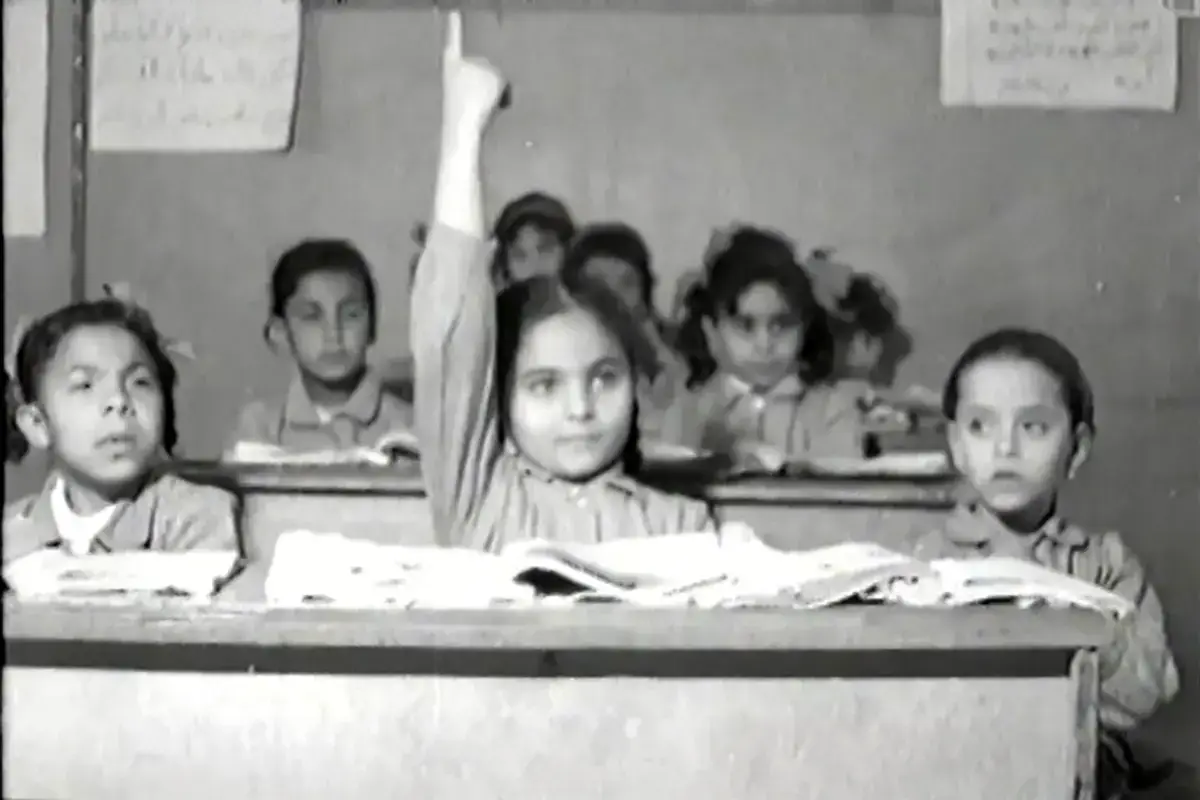

Image from "Looted and Hidden–Palestinian Archives in Israel"

This symbiotic relationship between documentary and research yields a bumper crop of new ideas and insights. Each field provides the other with fresh perspectives, challenging assumptions and opening up new avenues of inquiry. It is a virtuous cycle of intellectual growth and social impact driving both fields forward.

1. Rona Sela (2018) The Genealogy of Colonial Plunder and Erasure – Israel's Control over Palestinian Archives, Social Semiotics, 28:2, 201-229, DOI: 10.1080/10350330.2017.1291140 ↩

2. Roseanne Kennedy (2017) Memory Unbound: Tracing the Dynamics of Memory Studies (pp.47-64) Publisher: New York: Berghahn Books ↩